There are plenty of opportunities for us to move forward and abandon archaic practices, but we have to challenge the notion of mindset and challenge the adults in our school buildings to see and imagine schools that speak to the kids they serve.

Dr. Carlos Beato, Co-Director of Next Generation Learning Challenges

We recently sat down with Dr. Carlos Beato, Co-Director of Next Generation Learning Challenges (NGLC), to hear more about what difference he is most eager to make in education.

Q: What experiences informed your worldview of education?

Carlos: I look at education from two lenses, both connected to my own upbringing—being an English Language Learner and being undocumented—and how both shaped the experiences I have had.

I always tell the story of the time my fifth-grade teacher was walking around the class with applications to a specialized middle school, handing them out to students. I was going to school in the heart of New York City, where there’s this expansive application process.

I did not receive one; in fact, I realized it was never even a thought in anyone’s mind that I would be getting one. I would ask myself: “What was it about me? Why didn’t I receive a letter or an application?”

All of this was even before we had taken standardized tests for the year. It was just based on assumptions about who I was and what I was (or was not) able to do. I think part of it was that I had just transitioned out of a bilingual classroom (where I was doing really well) into a monolingual classroom. But, that was no reason to simply count me out of the process.

As a result, I never had an opportunity to even apply to one of the best middle schools in the Bronx and, instead, ended up somewhere that had the reputation as the worst middle school in the South Bronx.

For me, that experience really solidified the fact that certain kids were in the good classes with the good teachers, while others were not—and they were intentionally put in their separate spaces. I was fortunate enough that I was always in “the good classes with the good teachers.”

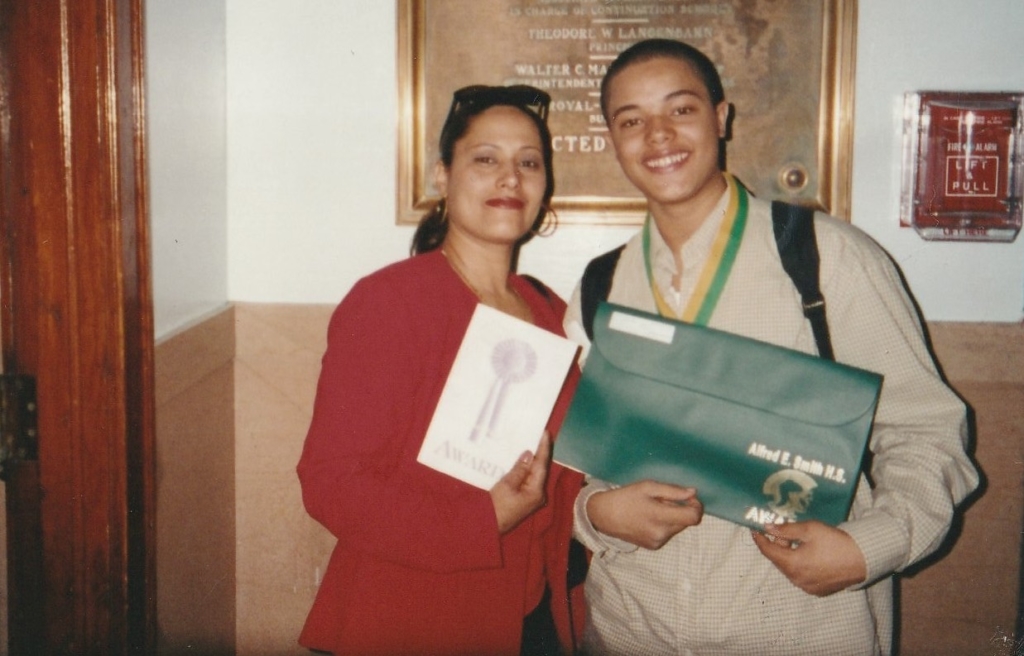

Carlos with his mom at an awards ceremony

Fast forward to eighth grade, when I remember walking into my counselor’s office and she said, “You’re the salutatorian this year.” I asked, “What’s that?” That question unto itself—my lack of awareness of even these relatively well-known academic terms—characterizes how I thought about myself in the system. I had no expectation that this kind of thing, that this honor, would happen for me.

All of this shaped my trajectory into education and what I saw needed to change, especially for learners like me.

For me, that experience really solidified the fact that certain kids were in the good classes with the good teachers, while others were not—and they were intentionally put in their separate spaces.

Dr. Carlos Beato, Co-Director of Next Generation Learning Challenges

Q: So, education was always the direction you wanted to take in terms of a professional career?

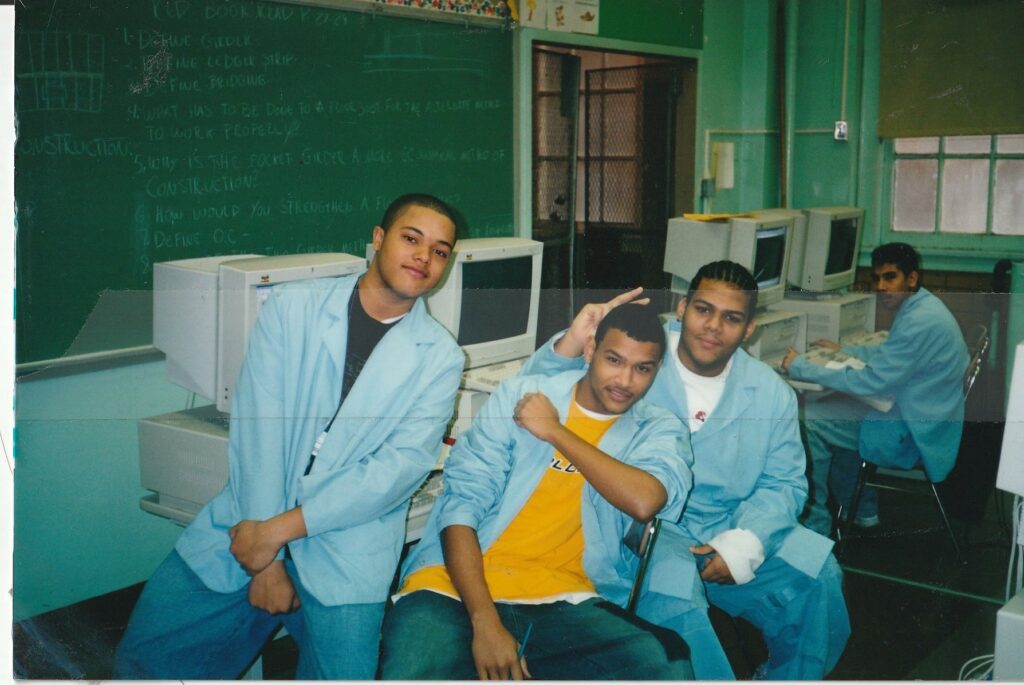

Carlos: Not quite. I went to a career and technical education (CTE) high school and was in pre-engineering and architecture. Growing up, I always wanted to be an architect. In fact, at the time, teaching and education were not even passing considerations for me.

I think this is partly because many immigrant families come to the United States with the hope and dream that their kids will become a doctor, a lawyer, or an architect. These are the types of careers that are sold to us as the way to get out of poverty and to make meaning of the education we have received.

I also enjoyed the idea of designing unique spaces, while using unique materials. I would study house designs, like those of Frank Lloyd Wright. I took a painting and architecture class at Cooper Union, as well as completed a two-year internship at a famous architecture firm in their interior design department.

Interestingly enough, it was these opportunities and the fact that they took me out of the Bronx and into the depths of Manhattan that got me thinking about how English Language Learners experience education and how we could do things in a more positive, profound way.

In these spaces, it was often difficult to come to terms with the fact that I was always one of a few people of color in the room. It couldn’t be that only white kids were interested in architecture. How, with the amount of Black and brown kids in New York City, did so few have access to these programs?

This question set me on a path to get at the root of the problem. I was not trying to tackle these issues within architecture, but it led me to pursue a career in teaching that was more aligned to the kind of change that I wanted to see happen for students that looked like me.

Q: How did you then get started in education?

Carlos: My “formal career” in education started as a founding teacher at a school for English Language Learners in the Bronx, called Academy for Language and Technology (ALT). Even as a young teacher there, I was driven to ensure that all young people, especially English Language Learners, were supported to be their best selves and enabled to be active participants in their learning journeys.

At ALT, I was fortunate enough to stay with my kids for their four years of high school. The kids I served ranged from those who’d had an interrupted education, having been out of school for years (some not even knowing the alphabet), to those who’d had amazing educational experiences in the countries they were coming from. From a traditional stance, it was quite difficult to find common ground from which to teach these different levels. This experience really forced me to see education differently and think about my own planning in a different way.

I saw how you had to build on each learner’s unique experiences and pathways—finding what would work for them and developing learning opportunities that could meet them where they are. And, because I stayed with them all four years, I was able to understand both them and their families on a deeper level. This really helped as I tried to create meaningful learning experiences for all of them.

And, even then, my interest in and ideas about architecture kept showing up—I wanted my young people to discover how to be “architects of their own learning.”

Q: What does that mean to you—to be an “architect of your own learning”?

Carlos: I think about the importance of literally building the agency of the young person. Learners need the opportunity to see themselves in positions of power—able to lead, design, and build their learning pathways.

If you think about adult learners, we don’t expect an adult to always be told what to do or exactly how to do everything. Adults are expected to explore, make choices, and pursue learning in ways that work for them. We shouldn’t give up on that when we think about young learners. Just following instructions, that’s not the way the brain is shaped to learn.

From my own experience, I’ve seen that pursuing project-based and competency-based approaches to learning are the most effective ways to enable young people to build and develop that agency and those skillsets they need to live full lives. And, to me, starting with a competency-based structure, in particular, is about being culturally responsive to learner and family needs and the way that education is shaped for them.

Q: Where have you seen this competency-based approach make the most difference?

Carlos: I really got to see this in action when in 2014, I was hired to design what would become the International High School at Langley Park (IHSLP) in Bladensburg, MD, which served an entire population of English Language Learners. IHSLP was founded on a competency-based structure. The school was actually one of the first schools in Maryland to take a competency-based approach and received incredible, vital support from Springpoint and the Internationals Network for Public Schools supported by a grant from Carnegie.

In that first year, our kids came from 27 different countries, spoke 14 different languages, and had drastically different levels of experience in an academic setting. We had to see each of these young learners as unique individuals; there was no way around it if we actually wanted them to learn. And, when you see each child as a unique individual, you recognize that their learning and skill-building develop in unique ways and see how important it is to think about their level of competency, rather than just their ability to score something on some test.

At IHSLP, we focused on four overarching areas: content skills, critical thinking skills, language skills, and social and emotional skills. Separating these out, we were able to actually support and assess young people based on what they knew and what they could do.

For example, maybe a learner is really strong in science but still early in their English language skills. In many conventional schools, that learner would be graded poorly in science because they don’t speak the language in which the test is given. But, with a competency-based approach, we enable them to demonstrate what they can do in science in their native language, understanding their competency development in English language skills is at a more nascent level.

With this focus on supporting the whole child and seeing the relevance of competency-based learning, we were able to really integrate learner feedback, even on the competencies and means of assessing those competencies themselves. For example, the ESOL department asked learners for feedback on the language rubric, and it resulted in a revamped, beautiful piece of work that had the young people’s ideas written all over it. These learners were empowered to be leaders.

There’s nothing like working at a place where you have a sense of belonging and where others have your back.

Dr. Carlos Beato, Co-Director of Next Generation Learning Challenges

Q: You’ve recently joined the NGLC team as Co-Executive Director. What drew you to the organization and what difference are you most eager to make there?

Carlos: NGLC helps others see, imagine, and put into practice the way we envision education to be. I was immediately sold from the first call with Andy Calkins (Co-Executive Director) when I was able to ask radically candid questions and get radically candid responses. Then, as I met others at NGLC, I was received in the same way. There’s nothing like working at a place where you have a sense of belonging and where others have your back.

There’s also the fact that I think NGLC is doing amazing work to help transform education across the country. I can imagine all of the other Carlos’ out there who could be positively impacted by having NGLC work with their teachers, school leaders, and districts.

The biggest difference I am hoping to make is twofold; I would love to help:

- Elevate the importance of having diverse voices in leadership positions in the field and how that might change some of the solutions we are putting out there; and

- Expand the number of classrooms and schools in the nation that bravely take on the challenge of reimagining education for the kids that they serve.

Question: What is the most pressing issue you see facing our country’s education system today? What possibilities do you see for ways forward?

Carlos: One of the biggest issues facing the education sector is that schools and districts continue to function in an archaic manner. For so many people, it has been generationally ingrained that education (and success in education) looks a certain way.

However, there are so many opportunities out there to make education more personal and that speak to the experiences of kids in their local communities; to make learning more engaging without sacrificing content or standards.

Our nation has to move forward and allow teachers to teach and not find themselves in the midst of political battles, which ultimately devoid our kids of having a well-rounded education. There are plenty of opportunities for us to move forward and abandon archaic practices, but we have to challenge and invite the adults in our school buildings to see and imagine schools that speak to the kids they serve.