What I Iove about our model is the community’s involvement in our students’ learning. We don’t believe our team of educators should (or can) hold all the knowledge our students need or want to learn.

Jess Canose, Educator, City of Bridges High School

Q: Why is “Real World Learning” a fundamental tenet of City of Bridges? And, what does that look like in practice?

Randy: We believe that human beings learn best by doing. This is reflected in my own experiences. I have a master’s degree and a doctorate, but my most valuable learning has been experiential—including teaching, being a principal, running a nonprofit, and other experiences such as baking bread or playing the banjo. So much of the learning that happens in conventional school systems is separated from the practice of life. We aim to bridge the gap.

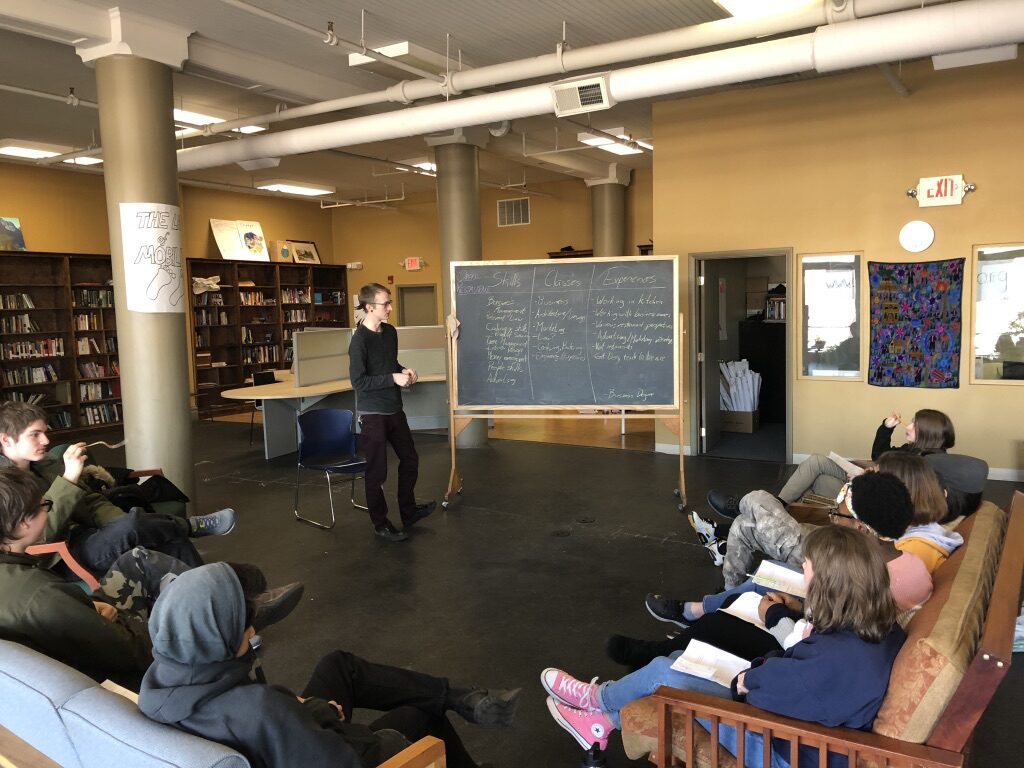

There are a couple of ways that we do this at City of Bridges. First, we have a Practitioner-Educator program where local professionals develop classes and projects with our students that connect the knowledge, skills, and understanding of school to the practical work of their profession. Our students have worked with game designers, physicists, defense attorneys, welders, writers, university professors, programmers, and many others.

Second, we have an internship program designed to help young people immerse themselves in possible future careers. The most important part of the process is exploring a young person’s curiosities in order to build relevant experiential internships that are meaningful and purpose-driven.

Justin: I feel that one of the best ways to learn is by allowing projects to be driven by a need in the community. As an example, we offered a Practical Computing class that combined cutting edge technology, an expert from the field of robotics, and a general question about the role technology plays in maintaining healthy cities.

We invited a practitioner from Carnegie Mellon University to teach us how to build things with Arduino—a piece of hardware that often serves as the heart and brain of a robot. Students learned how to use inputs (e.g. like flipping a switch) and sensors to create an output (e.g. like turning on a light) that was useful to them and the project they were working on. After learning the fundamentals of Arduino, students were able to build a tool to measure the air quality in the neighborhood and send the data output to an LCD screen. It’s great working with something fun and practical, like robots, in the context of investigating and improving our community.

Jess: Real world learning bridges unapplied knowledge with the practice of life. It reflects the type of learning we come across in higher education or trades where fields are no longer siloed into “core subjects” and, instead, have endless depth and many perspectives to consider. This is something I am especially excited about given my academic training (in food studies) is inherently interdisciplinary.

From our classes to the conversations we have during lunch, real world application is always present. For example, our Spanish class extended beyond language learning to discussions about immigration and border control—opening up the opportunity to discover and contribute to a local nonprofit’s immigrant aid program.

In Food Systems, the students decided to study chocolate, which led to exploring the craft of chocolate making, economics, agriculture, colonialism, child slavery, marketing, certification processes, and ethics. Class tastings and morning cups of hot cocoa emphasize the class’ relevancy. Creating personal connections to the learning and interweaving cross-disciplinary thinking opens up the many personalized paths students can consider taking today and in the future. And, it challenges conventional notions of what “counts” as learning or who the primary holder of knowledge is.

Q: How has a focus on real world engagement shaped your response to global conversations about racial justice?

Randy: This moment, surprisingly, has had a more substantial impact on our school than the global pandemic and the physical distancing. Two weeks ago, we would have had a different conversation about the moment we’re living in and what it says about education. The murder of George Floyd (and others) and the light it’s shined, once again, on the systemic racism and violence in this country has absolutely shifted and reshaped our approach.

During the last two weeks of our school year, as many of our students participated in local protests, we pivoted heavily to listening to the voices of communities of color here in Pittsburgh. We are being very intentional about exposing our students to voices that are not often present in conventional curriculum, including Dr. Terri Watson and Dr. Ibram X. Kendi. We have also been listening to podcasts on American policing from Throughline and Campaign Zero.

This inquiry into structural inequities and the role of race in our society will be central to our curriculum in the fall. It is part of the ongoing work to raise our awareness (as a school) and actively make positive changes in the community. It’s been incredibly inspiring to see our students as part of the national trend towards young people leading the movement for racial justice.

Justin: I love that we’re not afraid to make really radical changes in our plans to align with what our students need at any given moment. We constantly ask, “What do our students need right now?” This questioning and conscious pivoting shows up in many ways.

Earlier in the year, we set aside a day to participate in climate protests. We decided what was going on in the world—which we’re a part of—was more important than our classes. We carried that spirit into the pandemic and into our response at the height of the racial justice protests.

Our students had a foundation to build from before the protests began. During the first block of our year, we taught a civil and human rights class and a human-centered design class where we discussed how power works in our world. Deeply embedded in City of Bridges’ bones is the idea of lifting up the voices of people who have been historically silenced.

When the protests began, we felt It would be ridiculous—during this uprising against racial violence in America (and globally)—to ask students to continue with regular academics. Instead, we asked students to spend the remainder of the school year hearing and learning from voices of color. That mindfulness is what defines our school and gets me excited about working here.

Jess: Through our students’ coursework and project-based learning with external practitioners, we often focus on social justice and systems-level thinking from a local and global perspective. Reflecting back on the Food Systems class I mentioned earlier, our first learning expedition of the year explored the makeup of the food system in Pittsburgh—learning from professionals at local cooperatives, food rescue organizations, and farms.

In our class, these voices helped us to use food as a lens to understand sociology, health, politics, agriculture, power, and intersectionality. These general topics extended from conversations about food access to ones about the reverberating impact of colonization to others about the history of redlining and segregation here in Pittsburgh.

What I Iove about our model is the community’s involvement in our students’ learning. We don’t believe our team of educators should (or can) hold all the knowledge our students need or want to learn. We also understand the power that schooling has as an institution.

To that end, we want to be intentional about bringing in external practitioners, staff, and resources that represent the lived-experiences of the black community and other communities of color. We want to meet students where they are, while cultivating an environment of social justice thinkers, co-conspirators, and activists. And, we are committed to making space for daily conversations that honor our commitment.

Q: It’s clear your relationship with the community is critically important. Thinking back to when you initially pivoted to virtual learning, what strategies did you use to maintain that community connection?

Randy: We are a small, agile organization that was able to quickly translate a learner-centered, project-based, relational high school into a virtual format. It’s easier to make that transition when your culture already supports students doing independent projects.

As an example, this spring, a young woman set out to create a photojournalism essay on youth activism. After we moved to a virtual learning model, she shifted to documenting the experience of a team working together during the pandemic in Pittsburgh.

We supported her in adapting to what was happening in the world by facilitating a connection to a photojournalist from a local newspaper. The only element that changed was the ability to work face-to-face with the photojournalist. It’s a microcosm of how our school and the world have had to adjust to collaborating in digital spaces. So, thanks to our bond with the community, our work transitioned in sync with the changes that were happening within the workforce.

Having a relationship with the community is central to our commitment to honoring lived experiences. One way we practice honoring those relationships internally is by expressing appreciation for members of our learning community during our daily morning and closing meetings. We always start and end with gratitude and compassion. It was essential to maintain that practice as we pivoted to working from a distance. We have room to grow, and I’m eager to build on the personalization and flexibility we have explored during this time. But, I also feel good about what we accomplished.

Justin: Losing the direct contact we had in our normal school environment has been challenging. There’s a mental component missing. The simple act of walking into the school building prompts an automatic shift in your brain. But, we have seen how resilient our school community is the more we learn about the challenges other schools are facing.

At the beginning of the quarantine, we heard a lot about the experiences of families and students enrolled in the local public school district and compared them to our own. I recognized that the relational component we push so hard for at City of Bridges helped our students more easily transition to an online model. Creating genuine relationships allowed us to overcome challenges that were barriers in other settings.

Everything looked and felt different during the transition, but we were ready to take the necessary steps to adapt. Students learned they didn’t need a dedicated physical “learning space” to develop a habit of learning. They could still powerfully reflect on real experiences and the learning gained through them in physically distanced circumstances. This is a skill that will serve them well beyond their time at City of Bridges.

Jess: Working together to determine how much “screen” time would be valuable (considering our students’ different needs and home responsibilities) informed the balance we sought to strike between learning that happened during regular school hours and learning that happened outside those hours.

We also all offered some version of virtual “office hours”—providing an open space for students to discuss their studies, how they were feeling, or have virtual social gatherings. Some students made those regular check-ins, while others preferred phone calls. Continuing into the summer, I’ve been offering a weekly cooking hour on Friday or Saturday night where staff and students come together over Zoom to share cooking adventures and eat dinner together. To me, this adds a heightened sense of community, comfort, and shared commitment.

Q: Can you share one or two stories that capture the essence of what City of Bridges aims to provide to its learning community?

Justin: One of my favorite stories speaks to student agency—one of our strongest pillars. At the beginning of the school year, we started our day at 9:30 in the morning and went until 4:00 in the afternoon. At one point, our students expressed their frustrations about getting home so late and we opened up the opportunity to engage in a decision-making process, among their peers, to change it.

Once a week, the students discussed the idea in their governance meetings and decided starting at 8:40 in the morning was a better time. We honored their request and changed our daily schedule to begin each day at 8:40 and end at 3:30 in the afternoon. That’s our schedule to this day, and we’re proud it was a decision made by our students because we want to give them agency in the way our school operates.

Randy: We are intentional about bringing practitioners into the classroom to work on projects, but there are instances when, with our offered programming, we are still not meeting a student’s need or following their interests. When that happens, we give them the freedom to find another way to demonstrate their learning in a particular area. In the example of a practitioner coming in from Carnegie Mellon University to use Arduino, there was one student who had trouble learning those concepts through that approach.

The student decided she would do computer-aided design (CAD) design and 3-D printing to build a similar competency framework. Human beings learn in different ways and need different experiences to build the knowledge, skills, and understanding we need to be successful. Providing her that freedom and flexibility was responsive to her interests and the unique way she learns.

Jess: One of my favorite memories involves the first time I stayed for a closing meeting, which I usually miss as a part-time teacher.

I vividly remember observing students doing independent projects right up until 3:00pm, and being shocked when, as if on queue, someone picked up a broom and a dustpan. Everyone scattered to different parts of the school to clean before gathering again in a circle. I joined my first closing circle, wherein the students tossed a ball around, to share what they appreciated about each other.

I had never seen an environment where students maintained such close personal relationships and open communication. It was beautiful. Those small but powerful gestures acknowledge our shared humanity and a collective sense of space and belonging. It’s a reflection of who the students are as people and City of Bridges’ commitment to compassion and meaningful relationships.