Between the four of us co-founders, we have 18 kids. Right in front of us, we saw the variety of human beings who were experiencing the one-size-fits-all education system and quickly recognized it didn’t work for any of our kids.

Julia Burns, Co-Founder and Board President

Q: What unique paths led each of you to Pathways High?

Julia: I went to school for economics and then obtained a master’s in business administration. I worked in high tech for about a dozen years and then took a step back out of the workforce to have a family. I have five kids ranging in age from nine to almost 17. While raising my children, I became an active community and school volunteer. One of the activities I found myself heavily involved in was our Destination Imagination (DI) program.

Through that program, I, along with a few other parents, saw the power of unleashing the potential of diverse young people who bring a wide range of abilities and lived experiences. There’s a long story as to how Pathways came to open its doors, but we officially launched in August 2017, and Kim joined us as a consultant in February 2018 then as a part-time Director that June.

Kim: This is my 24th year in education. I began my teaching career in Milwaukee but moved away and began working in suburban schools, where I eventually worked in different leadership capacities. It wasn’t until I returned to Milwaukee and the urban schools that I began noticing a wide adoption of strict, compliance models within urban communities. I was like, “Wait. What the heck is going on?” This model that was being hailed as “what was needed” in urban schools to close the achievement gap seemed odd to me.

I spent 10 years in Milwaukee’s small K-8 schools that were labeled as “turnaround” or “start up.” I went in and out of drinking the standardized test Kool-Aid, while all the while knowing at my core that learner-centered programs would provide a more effective approach. The models we were supposed to be emulating were using a very prescriptive, directive program.

While I was trying to take our schools down the road of Lucy Calkins and more student-centered learning, I realized how difficult it was to implement this type of learning in a school where there’s constant turnover of both teachers and students. Add on the layer of your test results not matching expectations—because the tests aren’t measuring many useful things—and it becomes hard to remain a cheerleader for the model you know you should be implementing.

As my frustration grew, I happened to run into a friend (who was also an educator) who knew Julia. She could tell I was frustrated and likely ready to leave my current job. She told me she had this friend who was starting a school and that it sounded exactly like the kind of thing I was looking for. I met with the founders and, for various reasons, opted not to take the director position when they were first opening their doors. However, they were experiencing some first year bumps, and I came in as a consultant in February 2018 to help sort out some of the problems they were facing.

Q: Julia, what was the uniting factor between you and the other founding parents?

Julia: Between the four of us, we have 18 kids. Right in front of us, we saw the variety of human beings who were experiencing the one-size-fits-all education system and quickly recognized it didn’t work for any of our kids. This led to all of us wondering, why is it that we keep forcing this model on young people? What are we losing by prioritizing scale?

We wanted to create a school where kids could really tap into their unique passions, skills, and interests. When we looked at the DI experience, we saw the potential impact a system that is directed by the students could have.

I would say for all the founders, we saw so much squandering of talent in the existing system and when we look around and see the magnitude of the challenges we face as a country, we can’t afford to squander this talent. It’s untenable.

Q: What kept the group moving forward in designing and opening Pathways High when things weren’t going as expected?

Julia: Personally, I’m entrepreneurial. When I see a significant gap between what is needed and what is offered, I’m energized to pursue that opportunity. And, we had enormous support from the community. When we conducted our community conversations and built our network of support, we enrolled a lot of cheerleaders. Of course, there were naysayers and will continue to be naysayers, but their response isn’t directed at what we’re doing as much as it’s directed at the natural and uncomfortable feeling of seeing the status quo threatened.

Q: Kim, when you stepped in in February 2018, what did you immediately notice needed to be improved upon?

Kim: Structure was the first need that I wanted to address. Teachers and students alike had adopted a mindset that everyone could do anything they wanted to do. We needed to make the environment a physically and emotionally safe space for all kids to freely explore their interests and passions but, at the same time, develop clear boundaries for learning. Students needed to know and be held to expectations that were clear and reasonable. Oftentimes, too much freedom can cause paralysis and a sense of instability. When I enter a new school, I normally start with assessing the overall mindset of the community first, but I had to put that on the back-burner for the moment.

We experienced nearly 100% teacher turnover from our first to second year. When year two came around, and we had a better hiring practice in place, we started seeing the Pathways High vision come to life. We could better reflect upon questions like: Do we truly feel all kids want to succeed and how do we do that in a diverse environment? How do we create high expectations, and what does that really mean for creating common language?

Julia: Kim’s perspective as an outsider coming into Pathways was really helpful. Sometimes when you’re in the thick of it, you don’t necessarily see the obvious things that are right in front of you. Personally, I underestimated the extent of the change management that was needed. Some people are surprised we chose to start this work at the high school level because with younger kids, you have a longer time to mold them into the culture and you’re not inheriting the deeply ingrained mindset of the conventional system. I knew this would be the case for the students, but I didn’t realize this would also be true for the staff. Oftentimes with new charter schools, you have a planning year with your newly hired staff and get to build your culture before the students arrive. We didn’t have that opportunity. We hired and opened soon after.

The issues we faced were further exacerbated by the quick turnover of leadership we experienced, as it was difficult to find someone who had experience in learner-centered transformation within a diverse setting. That’s why Kim, with her experience in urban turnaround and start-up settings, has worked so well.

Q: Pathways High has been building their network with community and business leaders from the beginning. What recommendations do you have for learner-centered environments looking to build their own local networks?

Julia: I was frustrated with the disconnect between what was happening in the real world and what was happening in schools. I could see all of this innovation, compare it to what was happening in schools with my own children, and see how ill-prepared they were going to be for anything outside this bubble. For example, the local public high schools by my house are in close proximity to a regional medical center and college, but there was no interaction between these institutions. I knew from personal experience that when students are exposed to the rapidly evolving careers in any field and can build their networks, doors open to limitless opportunities.

I couldn’t help but wonder how there was such a big disconnect. That motivated me and the other founders to make sure we connected with a lot of different industry leaders, organizations, and the chamber of commerce before opening our doors. After listening to the needs of these employers, we knew the only way we were going to be able to do this effectively was if we continually exposed students to what those professional environments were like and, and vice versa, getting the business people into the school.

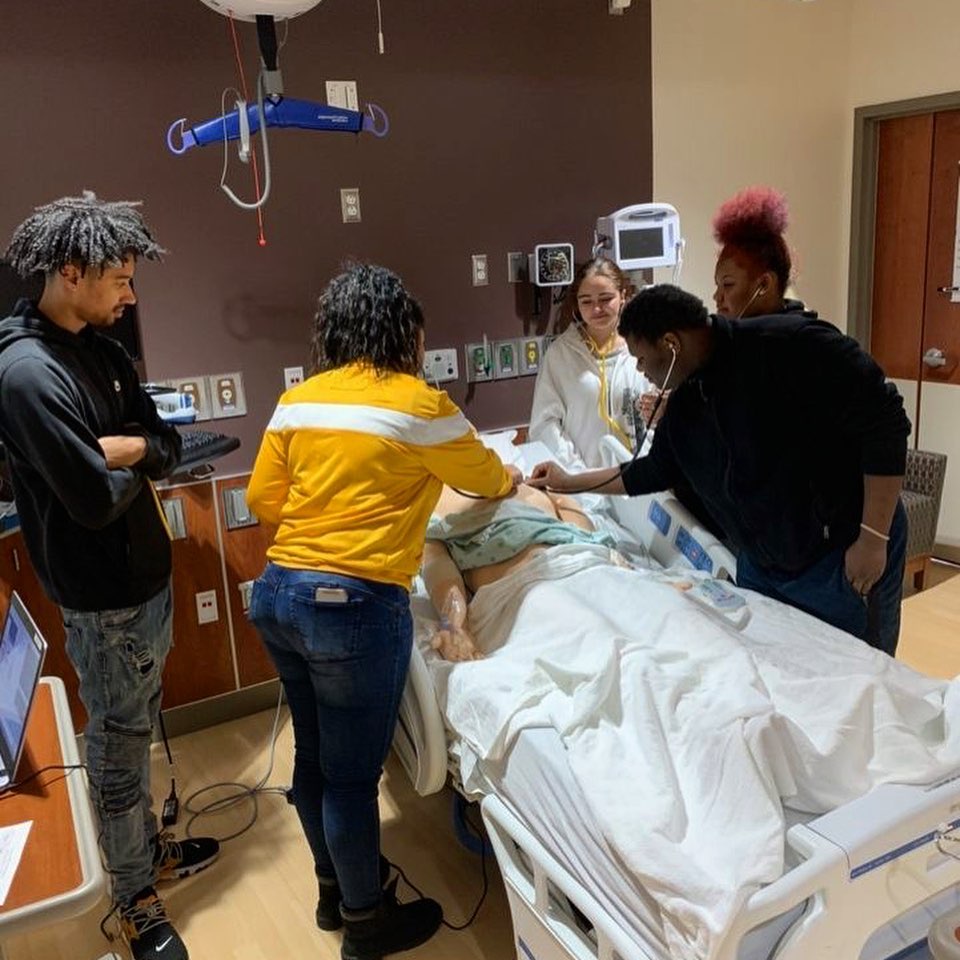

These findings led us to develop our IMPACT Program comprised of IMPACT experiences—real world learning where students engaged directly community and industry professionals—and an optional IMPACT Year. The IMPACT Year is a structured “gap” year after the conventional “senior year” for students who are still weighing their post-secondary options.

The piece that I think is important to think about is if you’re trying to implement this transformation, who’s going to own that over the long term? It can’t just be one person like an Impact Coordinator (a position we currently have). It has to be owned by every staff person and, ultimately, every student because they are the ones who are going to be the most passionate about whatever their interest is and they can then push out and find the resources they need to expose them to that industry.

Kim: Adding to Julia’s point about making this sustainable over the long haul, I would encourage others to think about how they can intentionally get everyone on board to share that responsibility. We have made it an expectation for teachers to have IMPACT experiences embedded in their seminars—nine-week interdisciplinary courses based on student and teacher interest. To start, this simply meant having relevant community and business leaders come in and speak about their work. Now, we are having teachers go into the businesses and shadow people, so they also experience these industries firsthand—getting out of their education bubble and building these community relationships themselves. In the first semester, we gave them the freedom to choose who they wanted to shadow. This semester we are partnering them with a business that we want to connect with more.

Q: What question do you wish you were asked more often about the work happening at Pathways High?

Julia and Kim: We wish people asked deeper level questions. People within and outside of education seem to be so interested in finding the magic bullets—the things that can be replicated. But, every community has a unique culture and population of students, meaning replication isn’t possible. There really is no magic bullet. You can do X, Y, and Z just like we did it, and it still might not turn out the way you expect it to.

The other question we wish more people would ask is: How can we build an equitable model of learning that acknowledges our diversity of students? How can we engage in the hard, uncomfortable conversations necessary to create something that truly serves all of our kids?

When we ask for the results upfront, we discount the value of the process or the journey that actually leads to the success you see we or other learner-centered environments are having. We feel like if people appreciated that more, we’d all be better off.