In learner-centered environments, students struggle more, in right-sized ways, and benefit greatly from the struggle.

Tyler Thigpen, Co-Founder and Head of The Forest School

I have the privilege of leading and sending my children to The Forest School: An Acton Academy in Trilith, south of Atlanta, Georgia. The Forest School — as well as our sister school The Forest School Online — is a racially and economically diverse-by-design, learner-led school with a mission that every person who enters our doors will find a calling that will change the world.

At our schools, Guides (our term for teachers) use learner-driven technology, Socratic discussions, hands-on projects called Quests, and real-world apprenticeships. Guides give badges not grades, questions rather than lectures, and mentorship instead of homework. We provide direct instruction for the younger ages but wean most of them off of that method usually by the age of seven. From there, we use the Socratic method, making fun learning games and challenges for learners, responding to their questions with questions. We do these things so learners get practice at learning independently, become people of strong character, develop key marketplace skills, and live together in an intentionally diverse environment.

In April of 2019, I received the following email from Brooke, a 12-year-old learner at our school who was struggling with math. Brooke and her parents gave me their blessing to share this with you:

Dear Tyler,

I am sending this email because I would like to talk to you about a situation that I have been running into with [my e-learning platform for math]. Unfortunately over the past couple months, I have realized that I haven’t been learning as much math as I should be. I feel like I am not learning anything, and that these past couple months I have just been wasting my time learning on a platform that I don’t understand. Anyway, I think I might have a solution to this problem. My [plan is] to put together a system that works for my learning type. I have some ideas and a proposal that I would like to get your thoughts on. Do you have time in the next couple of days to meet with me to discuss this more?

Thank you,

Brooke

When my team and I got Brooke’s email, we rejoiced. We felt Brooke was taking steps to shoulder the responsibility for her own learning in a way we had never seen before. The morning after receiving her email, Brooke’s Guide and I sat with her on rocking chairs at the front porch of our school. There, she pitched a new plan to learn math, including a revised set of goals, cadence, supports, and timeline. We gave her ideas for improvement and eventually “approved” her plan; but honestly, we think she would’ve taken this path with or without our blessing. She was hooked on learning her way, and she saw a path to make it happen. Fast forward a few years, Brooke is now in the 10th grade and is thriving.

Brooke’s story is just one of hundreds of similar stories we could share about moments where learners have taken charge of their own learning. How are moments like these cultivated?

Designing Schools for Active Self-Direction

Almost every week — through consultancies, workshops, or inspiration visits hosted by our Institute for Self Directed Learning — we talk with leaders and educators who want to move toward learner-centered models. The most common questions we hear fall into four categories: learning design, operations, stakeholder buy-in, and change management. The leaders and educators we’ve met love the idea of learner-centeredness because students can — in varied ways — enjoy more choice, set their own goals, have more autonomy, go at their own pace, study more of what they want, peer- and self-evaluate, and even make some of their own rules. But, they rightly wonder what to do with more traditional methods like giving lectures, explaining concepts, answering questions, choosing curriculum, setting due dates, grading, and making rules. Leaders wonder how to get unstuck, change their systems, and make it sustainable.

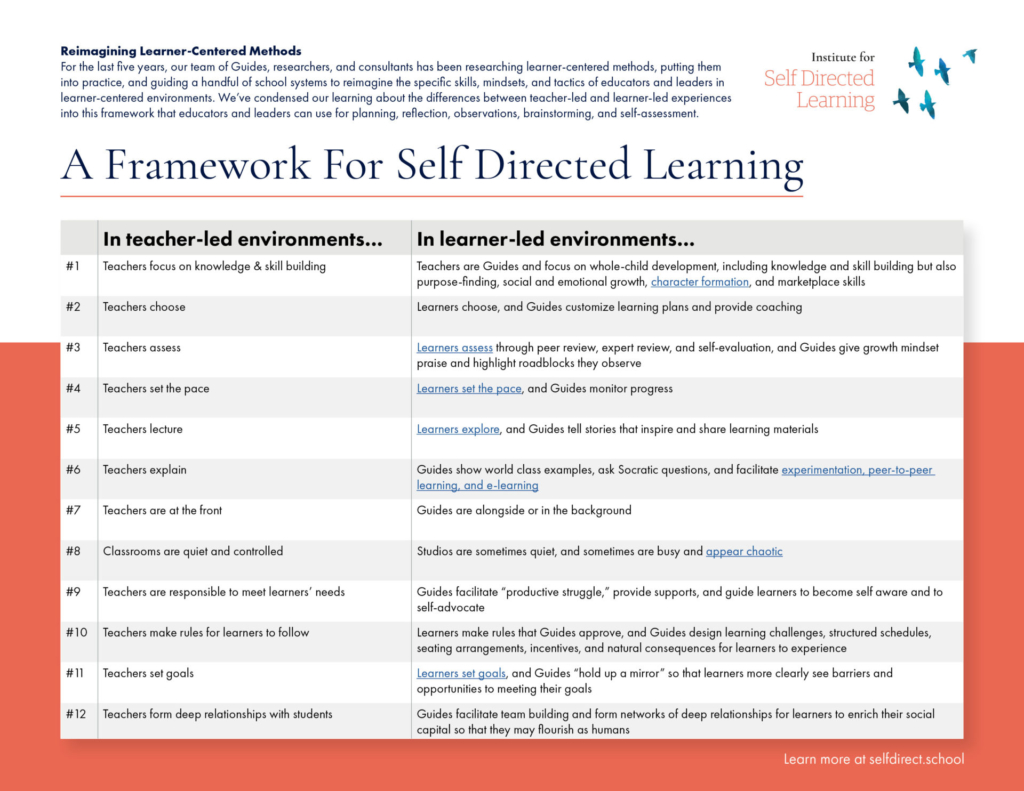

For the last five years, our team of Guides, researchers, and consultants has been researching learner-centered methods, putting them into practice, and guiding a handful of school systems to reimagine the specific skills, mindsets, and tactics of educators and leaders in learner-centered environments. We’ve condensed our learning about the differences between teacher-led and learner-led experiences into a framework that educators and leaders can use for planning, reflection, observations, brainstorming, and self-assessment.

A Framework For Self Directed Learning (Click here to download.)

We think of this framework as a series of spectra. For each component or row of the framework, one can imagine extreme examples on either end, as well as more moderate examples in between the endpoints of each spectrum. Our 2021 report on self-directed learning features illustrative examples of educator methods and active self-direction from diverse schools in the U.S. For many of the spectra on our framework, we have videos from our learners and staff to flesh out the implications (and have linked a few of them above). For each of the above spectra, educator methods look different according to the different developmental levels for each age or grade band.

We’ve seen that a key outcome of the work of school systems to move towards learner-centered models is an increase in classroom methods that allow for what researchers call “productive struggle.” Productive struggle is the process of effortful learning that develops grit and creativity.

Tyler Thigpen, Co-Founder and Head of The Forest School

If we had to summarize this framework into a simpler, unifying definition, we’d say self-directed learning (which is our go-to term for this approach) occurs when “learners — in the context of an interdependent community of peers, trained educators, and caring adults — choose the process, content, skills, learning pathways, and outcomes of learning, with the guidance, accountability, and support of others, in service of finding a calling that will change their communities and the world” (Kenner, Carlson, Raab, and Smith, 2021).

We’ve used this framework with educators and leaders to deepen their understanding of learner-centered approaches, brainstorm learner-led experiences for their unique classroom contexts (or borrow experiences from exemplary self-directed learning schools), identify barriers, and develop strategies and “key leadership moves” to address those barriers.

For example, at Pike County Public Schools, a rural public school district in Georgia of ~3,400 learners, teachers and school and central office leaders have embarked on a multi-year journey to invite their students and parents towards a more learner-centered environment. To do so, they’re working to align their widely regarded portrait of a graduate with their vision for teachers as guides, curators, and designers. Pike’s team has identified vexing barriers to moving their classrooms farther to the right on the spectra of learner-led experiences, including:

- Misconceptions about learner-led environments

- Lack of student confidence, motivation, and/or maturity

- The need for teachers to “make sure” students are understanding content

- Having to teach too much content

- Class numbers, tech resources, planning time, and making it relevant for all learners

- Public perception of what others think educators and students should be doing

- How hard it is for teachers to “let go”

Seeing the benefits of learner-led approaches, one teacher we worked with imagined how she could get started, despite the barriers, reporting: “I have a fear of letting go because my students are at such a foundational stage and so skills-based. This release is uncomfortable for me, but I truly want to dive in and bring this to life in my classroom. I think I will start with the great idea shared with us [by one of my colleagues]: ‘Teach the Teacher,’ ‘Teach a Friend,’ and then “Teach Yourself.’” Though not without its challenges, Pike’s leadership team is developing innovative methods to address each barrier.

Graduating Independent, Self-Directed Learners

From research, we understand that the predominant characteristics of a self-directed learner are a strong desire to learn or change, a love of learning and a high degree of curiosity, the acceptance of responsibility for learning, independence in learning, and self-discipline and self-efficacy (Guglielmino, L. 1977).

To help Pike and others, our Institute team has taken these characteristics and developed a beta tool called The Makings of a Self-Directed Learner, which doubles as an “observable traits” rubric for teachers and a simple survey tool for students. Students in grades 3 to 12 can use the survey at the beginning, middle, and end of a school year to understand what learner-centeredness looks and feels like and how they perceive they’re growing. Teachers and school leaders can use the survey and rubric to monitor progress of students over time. Our team is piloting the tool in public and private school settings this year.

We’ve seen that a key outcome of the work of school systems to move towards learner-centered models is an increase in classroom methods that allow for what researchers call “productive struggle.” Productive struggle is the process of effortful learning that develops grit and creativity.

Dr. Zoretta Hammond argues there is a dearth of productive struggle in U.S. classrooms today. She observes that too many learners “struggle because we don’t offer them sufficient opportunities in the classroom to develop the cognitive skills and habits of mind that would prepare them to take on the more advanced academic tasks.” This unfortunate reality is yielding graduating classes of dependent learners who are unprepared to do the flourishing, complex thinking and creative problem-solving that are required for life’s next steps. And, a disproportionate number of students living in poverty, English learners, and students of color are unable to work to their full potential because of ongoing exposure to rote memorization, undemanding curriculum, and a lack of exposure to productive struggle and freedom in learning (Orfield, 2001; L. B. Perry & McConney, 2010).

The good news is that it doesn’t have to be this way. In learner-centered environments, students struggle more, in right-sized ways, and benefit greatly from the struggle. Examples of productive struggle include learning how to manage time, minimize distractions, get into flow, make school work impactful outside school walls, design personal incentives, self-govern, and reconcile with others. Graduates of our schools have moved on into diverse settings including elite colleges (e.g. Georgia Tech, Howard, and Loyola), careers (e.g. acting and marketing), and gap year programs.

In our nation, many teachers and parents alike recently had a massive “aha” moment about the promise of students participating in active self-direction. If at-home learning during COVID showed anything, it showed whether and how much learners were dependent on adults for learning. Many students struggled without a teacher telling them what to do, when to do it, and how to do it. Learners with experience in self-directed settings prior to March of 2020 fared better because they had had practice with setting their own goals, working on e-learning platforms, and holding themselves accountable.

Since COVID, we’ve seen a tremendous uptick in interest for self-directed learning. The question before us all now is how education leaders might use that momentum to move forward, toward greater learning agency, rather than going back to “school as usual.”