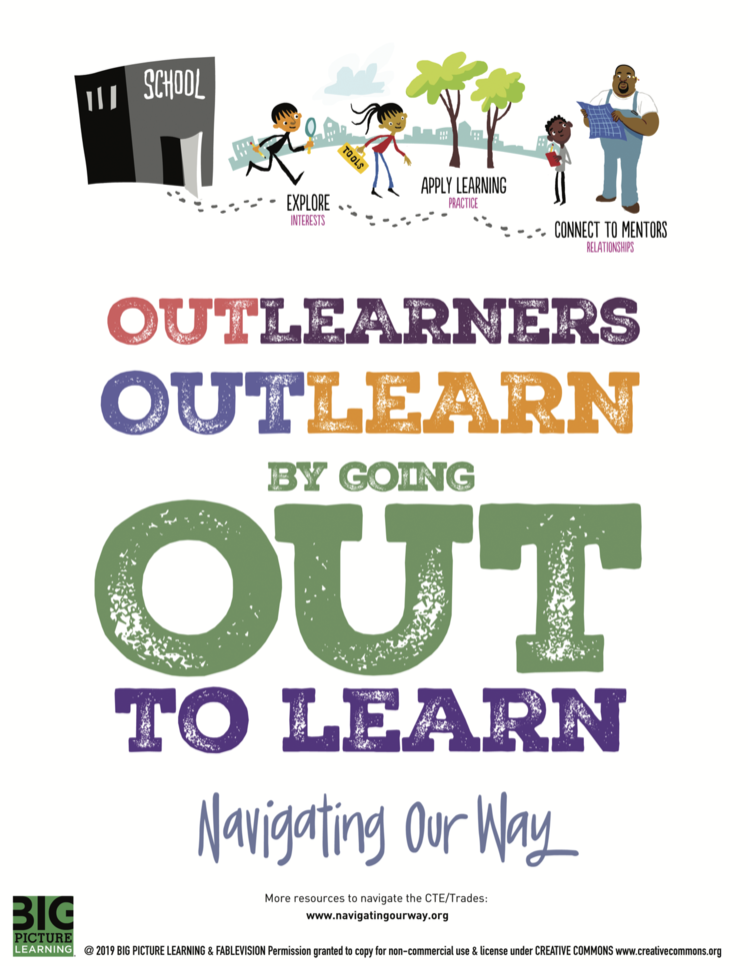

A guide, mentor, friend, and inspiration to me was community psychologist, Seymour Sarason. In-person and in his 2024 book, And What Do You Mean By Learning?, Seymour challenged educators to clarify the concept and context of learning. So often, learning is considered something that only happens in school or results from direct instruction or training. As humans, we are learning from the beginning. Toddlers who come to preschool or kindergarten have acquired a great deal of knowledge and competency in language and interacting with the world. Such learning, however, is not always adequately taken into account by conventional schools. Moreover, after formal education begins, the learning that happens outside of school is rarely considered by teachers and hardly ever credited by the system. Yet, out-of-school learning can be among the most highly formative, deep, and sustained types of learning, as well as the source of great motivation.

When schools allow students to engage in and navigate learning in their community—especially encounters that involve mentors and supportive adults—the potential for amazing learning experiences increases. Pioneered by John Constable in the early 1800s and made popular by Monet and his fellow impressionists, there is an approach to painting, called “en plein air,” which means “in the open air.” This form of artistic expression stresses the importance of actually being outside and interacting with the world when one is painting to best represent real, natural life.

A comparison to what was a revolution in painting is a natural allegory to today’s education. If schools want engaged learners who are experiencing deeper, thriving, and more self-sustaining partnerships, they need to seek what only fresh air can bring. In short, they need to let students out to learn by deepening local community partnerships in ways that go beyond classroom walls into the plain air of their local community and workplaces. It is here where students are “Outlearners.”

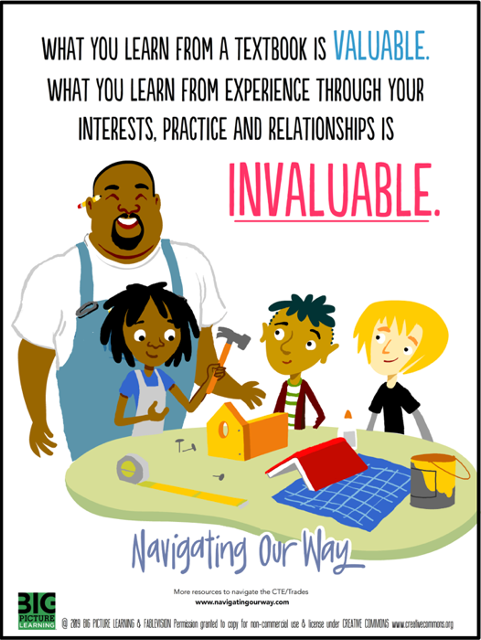

Whether you’re a teacher, parent, or youth development professional, as a supportive adult, when you connect Outlearners to real-world experiences, they encounter the messiness and complexity of their interests and projects. By meeting and working alongside adults in real-world situations, they learn how the world operationally defines rigor, observe adults doing high-quality work, and more deeply connect with knowledge and skills across disciplines through in-depth reading and learning driven by their interests.

In this more rarified air out in their communities, students who spend considerable out-of-school time on learning and work that they care about will benefit most. Once such a commitment is established, teachers, supportive adults, and students can more easily introduce the essential elements of rigor and vigor into authentic projects. These include complexity, breadth and depth, connections, tacit, and multiple academic disciplines, like reading and math. In doing so, we bring life to text and text to life. Through practice and projects with real-world consequences, students build three broad kinds of relationships—with people, with places, and with disciplines of knowledge. Teachers work with students to find supportive adults and mentors who are working on similar interests and projects in the world.

If schools want engaged learners who are experiencing deeper, thriving, and more self-sustaining partnerships, they need to seek what only fresh air can bring.

Elliot Washor

En plein air, Outlearners learn how to engage adults in serious conversations about their work, observe how they do their work, and learn their practice alongside them. They learn through the relationship, as psychologist Lev Vygotsky pointed out when he asserted that learning ability is guided by social interactions and that students’ potential for understanding expands through connection and collaboration with adults or more knowledgeable peers.

Learning out in the community, young people build social capital. What kind of problems do these adults confront doing their particular work? How do they go about solving problems? How do they network with others working on similar problems? Who is their community of practice? Teachers can also help students understand and pursue relationships between the focus of their projects and other disciplines. What students learn outside of school is deepened by what they learn inside of school and vice versa.

As Outlearners, young people can more easily address head, hand, heart, and health as one. When ideas are generated from en plein air experiences of making, manipulating, performing, and dealing with problems as they arise, they get a feel for the work through all of their senses and start to trust themselves and the ideas that emerge from working things out. This is the way, Outlearners get a sentient feel for the work that forms an idea.

For en plein air learners, teachers can employ assessment criteria and processes that accommodate the complexity of rigorous and vigorous out-of-school learning, including the processes and techniques that students employ to gain real-world certifications. When work is meaningful to a student, their communities, and to the world, they will set high personal standards pegged to standards deserving of merit in the real world that far exceed academic standards set by schools or governments.

When teachers and mentors employ a holistic approach to student-driven, real-world learning, the projects, tasks, and challenges are more complex and require increasingly more sophisticated work—processes, techniques, as well as products. The projects thereby enable an extraordinary depth and breadth of learning where the merit of the work is displayed not just in the object or project made, but by the transformation of the student doing meaningful work. This moves our assessment measures from just outcomes to “becomes” (that is, who the students are becoming through their learning). Many times, you will see engaged students redo their work over and over because they know they can do better by their own standards.

Ultimately, what schools and classrooms need to be about is enhancing students’ abilities to bring relevance and relationships to the rigor of their own learning. This will help them to understand how to employ standards of rigor to their advantage, first to their passions and interests, and ultimately to all of their learning and work both in and outside of school. Such capacities lead to resiliency as a learner and as a whole person. Getting relationships and relevance right prepares students to embrace learning opportunities where we turn rigor into how you mingle with people and ideas or how you muddle through problems around the things that matter to you. This gives vim, vigor, and verve to rigor as Outlearners become enlivened by engaging in their interests.

The relationships of Outlearners with people, places, and objects are key to healthy communities. Using the newest technologies like AI to support outlearning can play a vital role in managing, analyzing, and supporting community partnerships. Moving forward, successful educators must realize—just as educational historian Larry Cremin did decades ago—that schools are only one of many educative agencies. What we will all likely be trying to figure out in the next 20 years is the extent to which schools play the central or even most important role in learning for a child. The dynamics and culture of our world demand this type of inquiry, and we must realize that the answers to these important questions often lie on the other side of the schoolhouse door—en plein air.

For more information on learning in the real world, please visit B-Unbound and The International Big Picture Learning Credential.