[Learner-centered] means that each individual learner is honored for who they are and what they need because each person is different and unique.

Hazel Hales, Trailblazer, The Village School

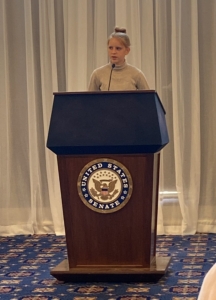

The following speech was given by Hazel Hales, a young learner at The Village School (TVS). The speech took place at the Kennedy Caucus Room in the Russell Senate Office Building as part of a Communications Challenge for TVS middle schoolers. You can read more about the full experience here.

Hazel Hales sharing the following speech in the Kennedy Caucus Room.

One Tuesday evening, my brother and his friend were rushing to finish their science project—because they totally didn’t procrastinate. They were printing out photos, gluing them to the poster board, and constantly asking if it looked good. I walked into the room and watched them work when I was prompted to ask, “Did you enjoy this?” Without hesitation or even looking at me, my brother responded, “No, it was just for the grade.”

Wow. I walked out of that room, feeling unsatisfactory, and it has continued to stay with me even in the present day. Maybe you can all relate to this. You worked on a project and didn’t enjoy it, but you kept going because you needed to. It was for a grade, and that grade was what determined your success in life. Learning has become for the grades. But learning shouldn’t be for the grades! Not only is a grade not an accurate measurement of intelligence, learning is important because it lets us know more about the world around us, and we should be driven by curiosity and a yearning to know more.

Since I joined The Village School last year, I began to wonder and ask more questions. As I learned and explored more areas of the world I didn’t know much about, like the Cold War or electricity, I was fascinated. This learner-centered environment has given me not only a love of learning, but other opportunities—like being able to build my own opinion, value others, shape my education to my needs, and honor each individual for who they are.

It’s important to understand what learner-centered education is and what it sounds like. The learning is centered around the person. It means that each individual learner is honored for who they are and what they need because each person is different and unique.

I want more kids to experience this learning because this is education done right. It should be accessible to kids all over the country, and the world.

A study conducted in New England sought to answer the question, “What exactly does student-centered learning look like in New England schools?” They asked the teachers what they noticed when student-centered principles were applied, and they found that kids were more engaged and focused because they had a say in their learning and this made it feel relevant to them.

One of my favorite parts of this learning style in this school is Civilizations, also known as “Civ.” As a brief explanation, we do thirty minutes of research on a topic, for example, Plato versus Aristotle, and write a 250 word essay on two Socratic questions. Then, we discuss it, and everyone can share their opinions on the question.

Civ has taught me two valuable skills. First, building an opinion. By answering questions about history I’ve gained new views and perspectives on big events, and it allows me to think for myself about them. Second, valuing and accepting others’ opinions. Sometimes in Civ, no matter how convincing or well-reasoned your argument is, people don’t agree with you. And that’s OK. People are going to disagree with you all through life, and it’s important to realize, accept, and value that. We shouldn’t shut down others because they disagree with us, but try to see things from their view to understand them better.

Not only does Civ teach me these important skills, but it’s also enjoyable! This whole philosophy of learner-centered education makes learning and being in school, appealing. And being excited is an important motivation. Learning shouldn’t all be strict. There needs to be an element of enjoying it.

No one on this earth is the same. Which means every learner is different. Instead of a one-size-fits-all conventional learning style, learner-centered education allows the needs of each individual to be met. For example, let’s say a learner’s strength was reading—she loved reading and was a total bookworm, but wanted to improve at math, which she wasn’t as good at. This style would allow her to focus more on math because she wanted to and knew she was already a skilled reader.

Or, let’s say that there was a kid with a learning difference. She could ask peers to read her the challenges, partner up, or explain things differently. It makes it easier to be a supportive peer.

This learning style is flexible to what you need. It honors you as a human being and individual.

This learning style is flexible to what you need. It honors you as a human being and individual.

Hazel Hales, Trailblazer, The Village School

I watched a great TED Talk by Jal Mehta called Less Schooling, More Learning. Immediately, he jumps into it with a bold statement, “Schooling is not the same as learning.”

He explained a study that he and his friend Sarah Fine conducted across thirty schools titled Good School Beyond Test Scores. What they found was surprising. As they asked students about moments in their learning that they remembered and experiences that had changed them, the kids never pointed to the core classes—math, reading, and writing. Instead, they pointed them to electives, extracurriculars, clubs, and places that explored what they were passionate about.

Mehta gave an example of a girl named Rose. She sat in her language arts class filling out a worksheet, matching the Shakespeare quote to the character that said it. But she was unengaged and bored. After the class ended, Rose went to her theater class, where she blossomed. She was directing and giving instructions to the other students. This was her passion, and she thrived and enjoyed it.

In The Village School, they push us to pursue what we are passionate about. We create skill badges for hobbies and interests that we have and want to explore more in-depth. For instance, I created a badge for crocheting, because that is something I am passionate about, and I wanted to learn a different style of it. There are so many different skill badges, from cooking to photography to languages to skateboarding, and this honors each person for their different interests and passions.

Mehta also mentions learning by doing, which is also something that is important in this school. We’ve extracted DNA from a strawberry, and built real, working electrical circuits! Building the circuits was my favorite challenge, even if it was difficult. We used mini LEDs, resistors, and breadboards—it was so cool! Then we got to put our working circuits in a city that we created out of paper. There was a gas station, a hospital, and even a Capital that was lit up with a red, white, and blue LED circuit.

Creating the circuits is more meaningful than doing a worksheet about it because it helps you learn it better, and creates valuable learning experiences that will stay with you. I know I won’t forget the Electricity Quest!

A couple of months ago, my friend Owen and I attended Education Reimagined’s SparkHouse conference. We learned what learner-centered means, how to tell people about it and make it known, and how taking action can help make it accessible to more kids.

Although the snack cabinet that we kept raiding was awesome, it was also inspiring to learn about other learner-centered environments. And I came back from that conference feeling incredibly lucky that I got to learn in this amazing school.

But that’s the thing: it shouldn’t be lucky. Everyone should have this kind of education available to them. I’m not just here to explain the problem. This is why I’m here: I want you to help. Something I’ve noticed is many people don’t know what learner-centered education is, or that it even exists! So, the easiest thing you can do—that I challenge you to do— is tell someone about learner-centered education. Share it with your friends and family!

We, youth, are the future, and we should all have this opportunity to learn right.

Thank you.