“The thing I love most about teaching here is that students are engaged in their learning and love coming to school.” That’s how teacher Joe Query describes working at the Methow Valley Independent Learning Center, a small alternative high school in rural central Washington. It’s also why the ILC, as it’s called, is one of my favorite schools to visit.

On a recent trip there, I talked with several students about their internships, projects, and learning plans. One had recently written an article for the local paper and was working with a non-profit to develop a substance abuse prevention curriculum for youth. Another wrote a $834,000 grant for her local church to install a solar and battery system to serve as a resilience hub during power outages. After the grant was received, her work shifted to collaborating with local adults to plan the installation and select the contractor. Her senior capstone project will be setting up that resilience hub and making sure the community knows how to access it during emergencies, such as prolonged wildfire evacuations that sometimes affect this area. Another student was researching early childhood development and psychology, observing three- to five-year-olds at a Montessori school under a mentor’s guidance. A fourth student was working on improving local weather forecasting, recently connecting with an Incident Meteorologist (I had to look that up) to explore ways to turn her work into a senior project relevant to the Methow Valley.

The ILC wasn’t always like this. Prior to redesigning itself about ten years ago with support from Big Picture Learning, the ILC focused on the accumulation of credits, primarily through a system of packets. At that time, the school consisted of a large room in the district’s bus garage, with a small glassed-in office in the back. Students would come in and take a test on the packet of that week, and that would count as adequate progress toward graduation. When you finished with a packet, you went to get another one from the teacher who occupied that little office. Truancy court was a key strategy to encourage attendance. Perhaps not surprisingly, attendance and graduation rates were persistently low.

In many ways, the old version of the ILC resembles our system of alternative schools at scale. It’s less of an intentional, coherent system and more of a patchwork that has evolved to address a perceived problem of students failing to thrive in mainstream schools. Recent data indicate there are some 435,000 students in public alternative high schools in the United States. That’s about as many students as attend public high school in states like Ohio, Illinois, or Georgia. Why don’t we hear more about such a large group of students? Dispersed as they are, and since they exist in the margins of their districts’ mainstream schools, students enrolled in alternative schools are often relegated to packet systems, credit recovery schemes, and other deficit-oriented strategies to get them to graduate without seriously preparing them for viable futures.

Whereas our collective national graduation rate is around 87%, the alternative school graduation rate may be as low as 24 to 37%, depending on estimates.

Following the shift to design around students’ interests and real-world learning, the ILC’s five-year graduation rate shot up to 83% after hovering for several years in the high teens. In the years following the ILC’s redesign, several other alternative schools followed suit with similar results. Lake Chelan’s alternative school graduation rate was 14% and now ranges between 70 and 82% for the past several years. Two larger suburban districts in western Washington phased out longstanding low-performing alternative schools and opened redesigned versions that have sustained high graduation rates for multiple years.

If I didn’t know better, I’d assume these students I met at the ILC were consistently overachieving kids who had always loved school but somehow ended up at the alternative school. But that’s not the case. The student studying child psychology described “completely plummeting” and “hitting rock bottom” in ninth grade at her previous school. “I felt like I had no motivation and no reason to keep learning.” Another said they started failing classes during the second semester of their freshman year. “No matter how hard I tried to learn the concepts they were teaching me, I couldn’t learn them. I literally had no friends.”

The student who was recently published in the local paper experienced similar challenges at their previous school. “I really was struggling at home and at school. I didn’t care to do any work. I would just sit in class and not listen and just be on my phone because I had this mindset that I was just stupid and wasn’t able to do as good as the other students, so there’s no point in even trying. Through all of middle school and freshman year of high school, I had pretty much all F’s. I didn’t turn in any assignments. They just kept pushing me up through grade levels even though I didn’t understand anything that I learned.”

The state’s data dashboard shows around 60% of the ILC’s students qualify for free or reduced meals (district: 40%), almost 29% have disabilities (district: 13%), and in recent years’ data as many as 25% have experienced homelessness (district: 0.4–2%). In other words, the ILC is sustaining high engagement and graduation rates for students facing significant barriers and previously identified as failing to thrive in mainstream schools.

It’s not that [students’] interests weren’t present before, it’s that school never asked about them. Now they love sharing what they’re working on, why it matters, and their next steps.

Jeff Petty

In my experience, the narrative surrounding alternative schools is often that they provide helpful interventions for students who otherwise would not be successful. But a 37% graduation rate sounds like a fairly unsuccessful intervention. And what does it mean to reach that threshold of required credits with no positive sense of yourself as a learner, no sense of purpose or vision for yourself, or how to apply what you’ve learned in real settings, and no network of adults who share your interests and know about your skills?

What has troubled me most about the alternative school narrative is the implication that something is wrong with the kids rather than the design of the schools they’re failing to thrive in. The ILC kids flip this assumption on its head. In the words of the students introduced above, “When I came to the Independent Learning Center, there was almost an automatic shift.” Another said, “I came here and it was like a weight lifted off my shoulders. I finally felt like I could engage in things I used to struggle with, like math. I am doing really well in math right now and I feel like I am really progressing. Now I love math!” A third said, “When I came here, I was really shocked at how much my peers were learning and what they were doing.”

As they tell me, it’s not that their interests weren’t present before, it’s that school never asked about them. Now they love sharing what they’re working on, why it matters, and their next steps. Many start telling me about their post-high school plans before I even ask. And when I ask them how the adults at this school learned about their interests? “They just asked.”

If you follow news about schools, you’re likely aware of mounting concerns about chronic absenteeism, low academic achievement, and adolescent mental health struggles. In recent congressional testimony, Rebecca Winthrop of the Brookings Institution linked all three to pervasive student disengagement. Multiple studies indicate that engagement declines steadily as kids progress through school, culminating with only about a third of 12th graders feeling engaged.

What can schools like the ILC tell us about how to build deep engagement into the design and culture of not just one school but our system of schools at scale? That’s the guiding question of Together We Learn, a statewide initiative in North Carolina recently launched by School Foundry and Open Way Learning.

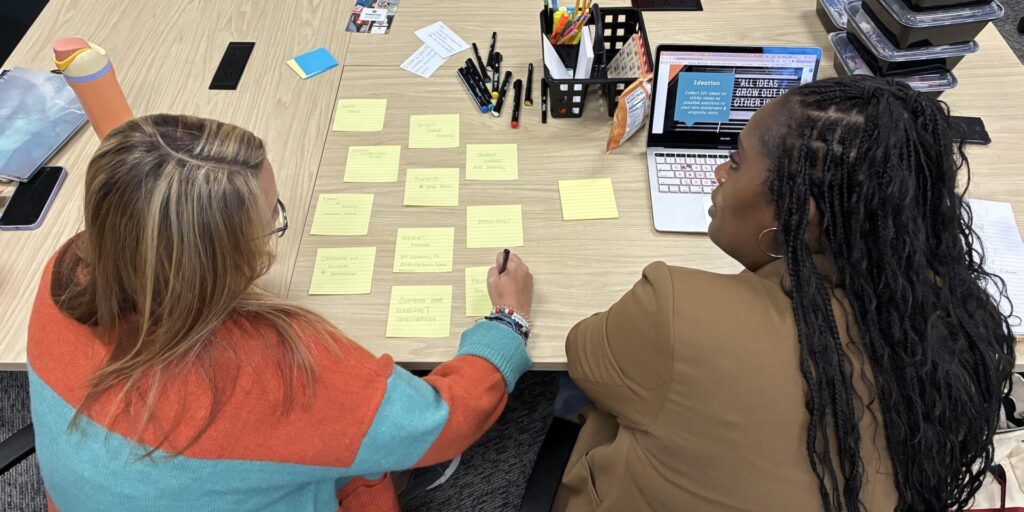

In October, teachers and leaders from alternative schools around North Carolina convened in Asheboro for an initial design sprint around revitalizing alternative schools. Participants from Wayne, Lee, Haywood, Halifax, Cleveland, and Randolph counties welcomed the notion of centering alternative schools as engines of innovation, as well as the opportunity to share with colleagues working in similar schools but who are rarely convened. The initiative envisions helping schools move away from compliance-driven and credit-centric approaches toward a more purpose-driven culture that centers students’ interests and goals and situates students’ project work in real-world contexts. As the project develops, participating schools will get on-site coaching and design support, convenings, and co-develop a peer network or community of practice to develop their own capacity. Not a new program, but different ways of organizing relationships and work.

Michael Crawford and colleagues at America Succeeds recently completed Phase 1 of a Research Practice Collaborative to explore how innovative schools help students develop durable skills, such as communication, creativity, metacognition, and collaboration. One of the schools in the study, Gibson Ek High School, is one of the aforementioned alternative schools in Washington state. Gibson Ek replaced a phased-out, low-performing program shortly after the transition of the ILC from a packet-based to an interest-driven model. Both schools’ transitions were supported by Big Picture Learning.

The America Succeeds study names five school-based practices that anchor the design of the innovative schools profiled: interest-driven learning, project-based learning, real-world engagement, competency-based learning and assessment, and intentional advising practices. This is educational jargon for what I hear from almost every student I meet who seems to love school. They are doing work they chose, work that interests them deeply. From their perspective, it speaks to who they are. They think and talk about their work in terms of projects; not the kind of project a teacher might design to teach a lesson, but the way adults define their work as projects. Their work is situated in the community outside school and has real meaning and impact that’s separate from school. As Jeff Robin, part of the founding faculty at High Tech High might say, these are not “dumpster projects” that get thrown away after the presentation. Their assessment practices are participatory, communal, multidisciplinary, and contribute to additional learning. And none of this is possible without extended intentional relationships (advising), because sharing interests and taking academic risks is vulnerable work and requires trust established over time.

Together We Learn is designed to leverage what we learn from kids who were “failing everything” in one setting and are now thriving in another. It’s about what happens when we ask students what they’re interested in, and how we design our schools to be ready to respond when they answer. We hope to support these conversations in a growing community of schools around North Carolina and connect those schools in networks of practice that keep growing and sharing what they’re learning, joining broader conversations and networks to sustainably improve lives and communities across the state. Imagine if every student had an education that asked about their interests.