This kind of reimagining—aimed at opening the door for real systemic change—depends on whether we’re asking the right questions.

Dr. Erin Raab, Co-Founder, REENVISIONED

In the history of public schooling, we have never encountered a moment like this—a moment where the normal daily routines have been interrupted for everyone at once. Amidst all the challenges this moment has thrown at us, we’re also presented with an incredible opportunity: we can step back and reimagine what the school experience could be and what we want it to be. We won’t be the first to reimagine school, but we can be the first to do it on a national scale.

This kind of reimagining—aimed at opening the door for real systemic change—depends on whether we’re asking the right questions.

Why Asking the “Right Questions” is Important: Lessons from a Space Race Fable

Have you heard about the race to create a space pen?

The story goes that in the 1960s, NASA was facing a challenge: traditional pens wouldn’t work in a zero-gravity environment, but astronauts needed to write. The NASA engineers asked, “How can we design a pen that writes in space?” They jump started their brilliant minds and got to work. Months went by, tens of millions of dollars were spent, and voila: a beautifully designed space pen was invented and produced for American astronauts.

Meanwhile, the Russians asked a different question, “How might astronauts write in space?” Hours went by, a few dollars were spent, and voila: they had all the space-approved pencils their astronauts would need.

Although the story is fiction, the lesson is very real: asking the right questions is the most important part of problem solving.

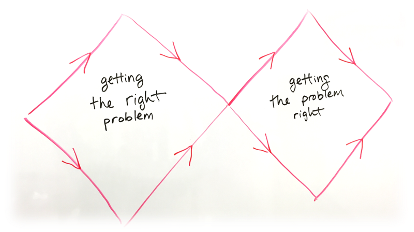

In design thinking, there are two main phases to solving a problem: getting the right problem, and getting the problem right. By far, the most important phase is getting the right problem.

Albert Einstein is famously quoted as having said, “If I had an hour to solve a problem and my life depended on the solution, I would spend the first 55 minutes determining the proper question to ask, for once I know the proper question, I could solve the problem in less than five minutes.” Coming from the man who could not get a job in academia when he graduated, but went on to forever change our understanding of the universe, we may want to take this idea to heart.

Yet in education, we have a history of rushing to solutions—we are busily “innovating” in getting the problem right without asking if we are addressing the right problem.

What’s the right design problem for schooling?

During the pandemic, states and schools have put considerable focus on questions like:

- How do we make sure students continue learning?

- How do we make sure students don’t fall behind academically?

- How do we ensure equity of access to the curriculum?

Each question assumes the problem to be solved by school is acquisition of content knowledge by individual learners. Yet, content knowledge acquisition is not the primary design problem to be solved by schooling.

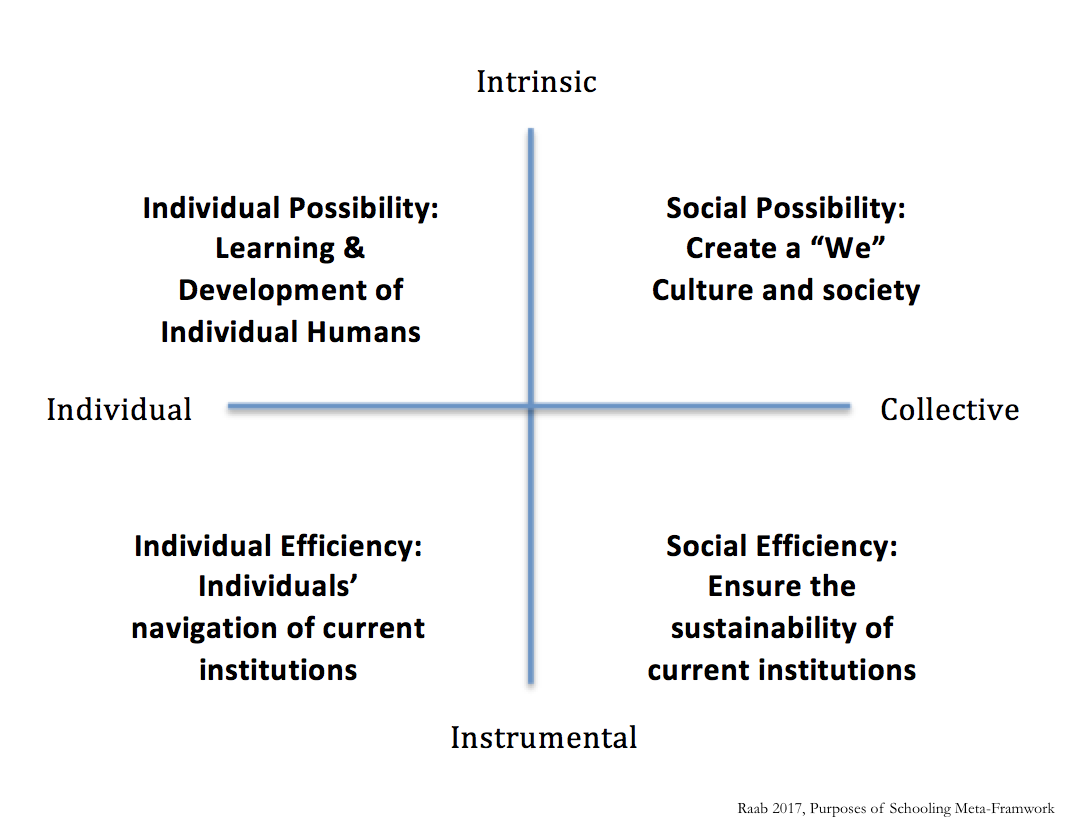

At REENVISIONED, we’ve found it useful to think about the four different purposes or lenses of schooling that are commonly used to frame research, practice, and policy. There are individual and collective purposes for schooling, and instrumental (efficiency) and intrinsic (possibility) purposes, that can be mapped on to a 2×2 as shown.

When we think about education as a design problem, possibility (not efficiency) should be our focus. But, both the individual and collective possibility purposes require a vision. They require us to ask core questions about what we want for our individual learners in schools, and what we want for our society.

What do we want for children we care about?

Implicity, we know school is about more than acquiring content knowledge, yet we rarely bring it into our discussions about outcomes or practice. At REENVISIONED, we have spoken with hundreds of students, parents, educators, and education leaders about their hopes, dreams, and fears for children they care about. We ask them about what it means to live a “good life.” Molly Wertz, then Executive Director of Tandem: Partners in Early Learning, spoke about her granddaughter and answered in a way that captured many elements expressed by other participants:

“School should help her know herself. It should help her know her power. It should help her find her sense of responsibility and community. It should offer her access to inspirational guides. It should offer her skills to be able to fully embrace and utilize the information that exists in the world, and it should offer her access to great thinkers and great teachers, and the intersection of ideas.”

Broadly, when participants talked about kids they cared about, they did not speak just of content knowledge. Participants spoke of activating an Aristotelian sense of flourishing as agency: the ability to make informed choices about the options available to us in a way that’s aligned with our own unique constellation of values, strengths, and preferences.

This is aligned with the notion of flourishing found in both philosophy and social psychology: we flourish when our core needs are met, we have the freedom to make choices about our lives, and we find our choices to be meaningful and fulfilling.

Everyone interviewed wants the children they care about to flourish, now and as adults.

When presented with the idea that we need more than just content knowledge to flourish, many people say, “okay, fine, supplement content acquisition with social-emotional learning or character programs.” There are a few major misconceptions embedded in this reaction. First and foremost is that it ignores that character building and social-emotional learning can’t be contained in a single class period or through a supplemental curriculum. It’s happening all the time.

The conventional K-12 system has learners spend about 14,000 hours in school. If our future selves are created out of who we practice being today, as both Aristotle and modern neuroscience tell us, then the habits and ways of being they practice in school will last a lifetime. These include habits of how students relate to themselves, their learning, and the world; and, habits of how they relate to others, co-create, and participate in communities.

So, what might we create if we ask ourselves: What are the capacities, character, and beliefs most needed for flourishing? Who are learners practicing being while in school? How might we design the schooling experience so that they practice—daily—the kinds of capacities, character, and beliefs we hope will lead them to flourish as adults and citizens?

What kind of society do we want to create through schooling?

We want children we care about to flourish. And, we need to remind ourselves that flourishing is not an individual act. We flourish (or don’t) within our communities and larger society. Aristotle appends his ideas of flourishing as personal agency by noting that for flourishing to be possible a person needs to live in a society in which they have both the freedom to make choices and their basic needs are met. Otherwise, all of our choices are oriented towards meeting basic needs, which is not true agency.

This idea that schools help create society writ large was actually part of common schooling’s original purpose. While reformers often speak to schooling having arisen in the manufacturing era, common schooling actually predates the industrial revolution. The original purpose of school in the U.S. (and the world) was not to create workers, it was to create citizens: to socialize children into a larger shared identity.

In U.S. schools, we become an “American,” and through this identity, we are part of a larger imagined community of fellow citizens we’ll never meet from Alabama to Wyoming to California to New Hampshire. School is our primary public socializing institution—it’s the way we come to feel we have something in common as citizens that’s bigger than ourselves and our immediate communities. “E Pluribus Unum”: out of many, one.

Thus, school is where we send our children to develop their individual potential, and where we create our society by establishing social norms, culture, and perspectives on the world and by socializing individuals into a larger collective.

This has implications for the structure, funding, and practice of schooling. Current reform efforts focus on designing for individual learning, or even individual potential, but too often ignore the opportunity to talk about our goals and vision for creating community.

When we forget about community and only focus on individual outcomes, we undermine our ability to thoughtfully design for the kind of community we want to be and become. I don’t think it’s a coincidence that this framing for the purpose of school went out of fashion in public conversation around the 1970s, and a generation later we’re facing a moment of dire threat to the function of, and faith in, our democratic institutions.

So, what might we create if we ask ourselves: What does it mean to be a thriving democracy? What implications does creating schooling for a thriving democracy have for how we fund, who manages, and where we locate schools or education more broadly? Within our school communities, what does it mean to practice justice, to practice fairness, to practice collaboration, to practice democratic deliberation, to practice collective liberation?

In a democracy, creating a shared vision requires asking beautiful questions and inviting people from different walks of life to participate in a reflective process. In other words, it takes engaging directly in the practice of deliberative democracy. It requires a process, not a one-and-done solution or program. And, it needs to happen at every level—from the local to the national.

What might it look to powerfully engage in these kinds of questions as a school community?

“There is no power for change greater than a community discovering what it cares about.” —Margaret Wheatley

A Process to Consider

At the classroom, school, and community level, REENVISIONED has been piloting a learner-centered re-visioning process that takes on these challenging and important questions in multiple states across the country that we’d like to offer to the broader community.

The basic process is that learners interview peers and adults in their lives (educators, parents, community members) and, instead of asking limited questions like, “What would you change about school?”, they ask each other big, brave, reflective questions about their full “theory of change” for school and society at-large.

They ask about what makes a good life, what kind of society they hope to live in, what the role of school is in helping create those lives and society, how well their own school achieves/achieved these goals, and their most empowering learning experiences.

Then, learners collaboratively code and analyze their data, make sense of the stories, and develop a shared vision for their school community that they can use to discuss changes with educators, administrators, the school board, and beyond.

Through this process, learners develop interviewing, listening, and data analysis skills, and they learn how different perspectives can be integrated into a collective vision. As a bonus, if they choose to, they can share their work with the world as part of the bigger movement to catalyze empathy and perspective taking—and emerge a new shared national vision for schooling.

The Process in Practice

While the high-level process remains consistent, its implementation is designed to be flexible and adaptable to whatever time and resources are available to the community. The process might involve one classroom or the whole school—a few interviews or 1,000. A group of learners might spend one day or a full school year engaging in this process. The recommended timeline and who is involved depends on the goals a community has for the process (REENVISIONED would be happy to be a thought partner in the design!).

As one example, in Palo Alto, California, a high school used an entire semester to engage in the process. First, journalism students learned the ins-and-outs of conducting a good interview and applied their knowledge by interviewing students, teachers, and other adults. Then, statistics students learned how to analyze qualitative data as part of their course. Deanna, the stats teacher, remarked:

“This…work in partnership with REENVISIONED was honestly one of the most rewarding activities of my career. The students were interested and engaged, both in the process and in the content. They asked thoughtful questions because they saw themselves in these interviews. The work was personal, it was community-building, and it mattered to them. On a curricular note, I would also add how special it was for statistics students in high school to engage in qualitative coding. This is just not typically part of high school curriculum, and all the students benefited from the exposure to this data analysis tool.”

Students were surprised to find that many of the interviewees shared a similar skepticism about the way “success” was framed in a school environment—excelling in as many advanced courses as possible and getting into the best college.

While they had originally felt alone in how they wished school could be, they discovered many of their peers also questioned the dominant narrative. One of the students remarked, after they wrote to the principal about the process, their findings, and their recommendations:

“This research is highly important for us to find out what students think about success and how we can potentially use their input to better our school. By having open discussions with administration about the results of the interviews we conducted, we will be able to create an environment at [our school] that is positive for all students.”

Personally, working with young people and educators around these questions has been one of the most rewarding experiences of my career. These discussions bring tears, laughter, moments of pause, and deep insights. And, they help us reframe how we think about what we aim to do together in and through schools.

Final Thought: The Art of Asking Beautiful Questions

In poetry and philosophy, there’s a notion of the “the beautiful question”—rather than being limited, beautiful questions open our horizons, cause us to pause and reflect, and encourage us to reimagine possibility. Poet David Whyte says, “These questions ask us to reimagine ourselves, our world and our part in it, and have the potential to reshape our identities, helping us to become larger, more generous, and more courageous, equal to the fierce invitation extended to us as we grow and mature.”

As we consider what to do with the potential of this unexpected, difficult moment, I hope we’ll begin asking the kinds of beautiful questions of ourselves and our communities that will help us create real, positive, systemic change for our learners and for our society.