For my children, having a parent always in their ear reminding them of their boundless potential to be great forces them not to settle for the lie that society perpetuates about the limits of Black boys’ and men’s intellectual potential.

Dr. Craig Waleed, Educator, Counselor, Motivational Speaker, and Author

This is part two of a two-part conversation with Dr. Craig Waleed, author of Prison to Promise: A Chronicle of Healing and Transformation (read part one here). At 19 years old, Dr. Waleed was sentenced to four to 12 years in prison, where he began a personal transformation journey that led him to earning a master’s in mental health counseling and a doctorate in executive leadership. Today, he remains focused on empowering others like him to shape a more hopeful future of their choosing. We are honored to share his story.

Q. When you hear the word “school,” what memories spark from your childhood?

Dr. Waleed: As a teenager, school (both the private Christian schools and suburban schools I attended) was a place where I constantly felt anxious, frustrated, and angry. I was a pretty smart student, but the problem was there often weren’t many Black kids, administrators, or teachers present.

People didn’t know how to handle me, or they chose to handle me in ways that retraumatized me. Because of that, I didn’t apply myself [in school]. I was more concerned with having swagger and being known as the tough guy. I was blatantly disrespectful to classmates, administrators, and teachers.

I didn’t really understand myself then and became unruly. I don’t think my mom and others who were responsible for raising me understood how the trauma of those experiences impacted my cognition and behavior. Looking back on my life, I realize my behavior was a defense mechanism for coping with the anger and fear associated with being in those spaces.

The only time I did well in school was when I wanted to stay on the football and basketball teams. I didn’t see a future for myself beyond that. I eventually started going hard towards the streets, drugs, alcohol, and criminal activities. I often showed up to school inebriated. That’s what I saw as my future. Still, I somehow managed to graduate.

When did you discover Black intellectualism, and how did it change who you wanted to become?

Dr. Waleed: I met some of the most brilliant men during my time in prison, but I don’t think many of them realized how brilliant they were until they found themselves in this place where they didn’t have as many distractions. They were forced to face themselves. I saw myself in them and in the books I started to read.

The first Black intellectual I read about was Carter G. Woodson. I was blown away. I remember thinking, “Why have I never heard about this guy? If he did that, I can do that, too.”

Then I started reading more literature about Black history—literature that ventured far beyond what they taught us in school. I was reading about historical figures like Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. and Malcolm X and began to see all the amazing contributions Black people made toward advancing human civilization—and even here in our own country, where generations of ancestors were enslaved. So many of those men and women still committed their lives to creating a better world for everyone.

I started to realize that I have the same potential within me. It’s strange because, similar to when I was a kid, a lot of young Black kids growing up today are conditioned to believe that being intellectual means they’re trying to be white. They equate [being smart] to not being your true self. Lots of young Black children, sadly, are being cut off from that part of themselves and convinced to remain true to something that isn’t real.

I think that’s part of the legacy of slavery that still follows us. During that era, the Black folks who were most celebrated, recognized, and permitted to sit in affluent spaces, next to people of influence, were usually entertainers and athletes. Today, many young Black children still see those routes as their only vehicles to achieving success.

It’s okay to run, jump, and have an interest in sports and the entertainment industry, but I think those interests should be secondary. It should be more about developing and expanding our potential to think and exercising our brains more than our bodies. My sons and I don’t watch a lot of sports because I want them to dream bigger. I want them to understand that if they can think it, believe it, and have the guts to pursue it, they can achieve it.

Q. You speak passionately about the limited expectations society holds for Black boys and men. Do you have conversations about racial justice with your own two boys?

Dr. Waleed: I have two sons, ages eight and 14. We have some of those conversations; more so with my older son. He’s really informed. However, I try not to talk too much about racial injustice and the inequities in this country because I don’t want them to carry my burdens or to see the world the way I see it.

In many regards, my perspective of the world is jaded because of my own experiences. I want them to have the capacity to recognize injustice and confront it when necessary. And, I want them to feel empowered to help make the world a better place. Right now, I want to protect them by not exposing them to things that might interrupt their dreams.

My wife’s from another country, so, sometimes when I talk about race matters, my views don’t make sense to her. This is in part, because she’s never had the same racialized experiences as me. Being Black in America is a unique experience. If she’d gone through some of the things I’d been through, she might’ve lacked confidence and been less successful.

I want the same for my sons. I don’t want them constantly thinking about what their dad went through and being afraid they’ll be hurt in the same way. I want them to realize that the world is wide open.

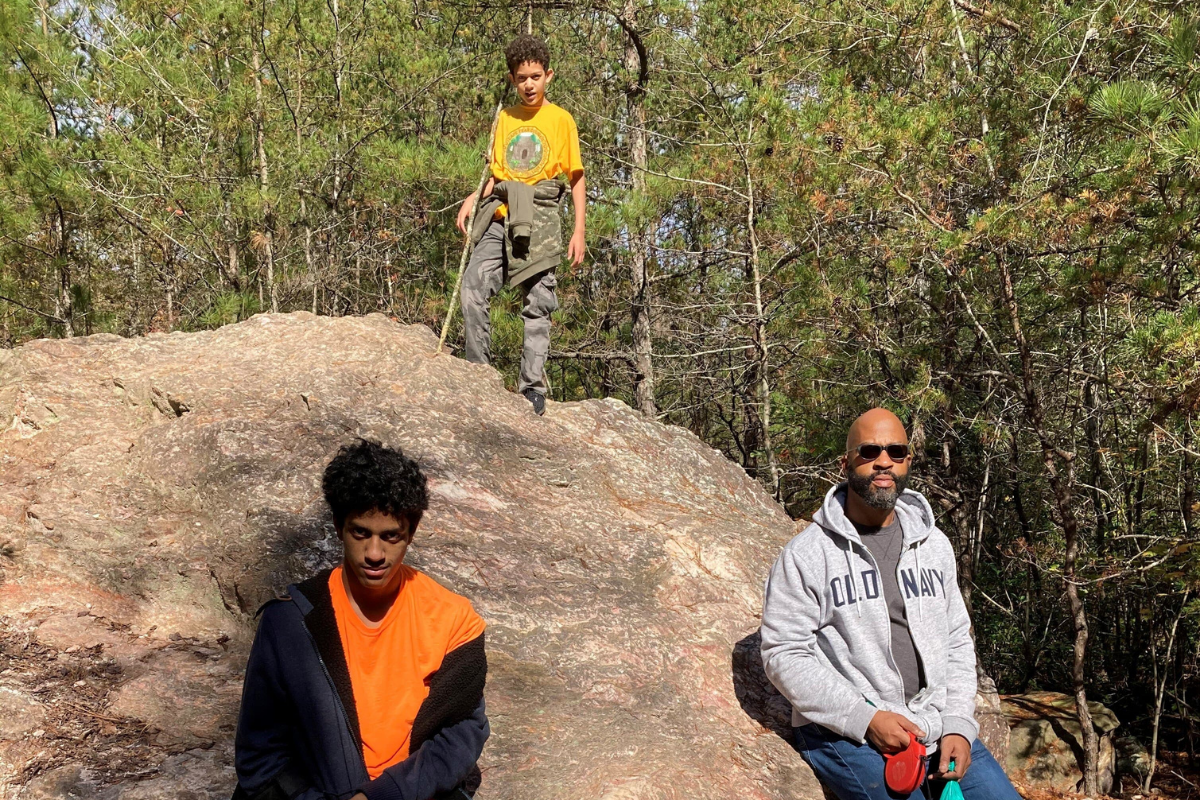

Dr. Craig Waleed with his two sons exploring the outdoors

Q. What are your kids currently interested in? How do you push them to pursue those interests?

Dr. Waleed: My 14-year-old is in ninth grade, and he is getting kick-ass grades in science, math, and political science. My eight-year-old is more into athletics and is more hands-on with his learning, but I’m pushing academics with him as well. I’m always telling him, you can become an engineer, designer, or architect. Really, I’m trying to shake their minds free of limited thinking and help them look beyond the surface.

My ninth grader wants to follow politics or science, and he’s really into anthropology. My eight-year-old wants to be a construction worker; though I continue to tell him he can be a construction engineer—the guy who designs how the building is constructed or deconstructed.

I think all of us have great potential within us, more potential than we know. For my children, having a parent always in their ear reminding them of their boundless potential to be great forces them not to settle for the lie that society perpetuates about the limits of Black boys’ and men’s intellectual potential. The sky’s the limit, and I say that because I love my boys. And, I think they’ll take my word, over society’s or their teachers’.

Early in my life, I was robbed of that opportunity partially because the people who were around me couldn’t see that far in their own lives. They wanted to make sure they had a job and a check coming in, so they could pay the rent. I want to enable my boys’ dreams to not be limited by the need for survival.

I also want to spread this hope and insight to all young children, especially those from Black and Brown communities. I want them to know that wherever they come from, they don’t have to remain on the margins. They can be a creator. They can have a positive impact on this world. But, they have to believe it.

We need to help young people grow and gain access to the opportunities that help them develop their own ideals and worldview. Too often, young people who come from underserved and impoverished backgrounds, schools, and neighborhoods don’t have enough resources available to support their dreams. The greater access one has to resources, the more likely they are to broaden their thinking and reach their potential.

Q. If you could rebuild education tomorrow from the ground up, where would you start?

Dr. Waleed: What immediately comes to mind is what I learned about ancient Egypt. In that civilization, there were only a few people permitted to learn how to read and write and study the sciences. But, the first tenet of all their knowledge, and what was written above the doors of their places of learning, was the inscription: “Man, know thyself.”

The first building block of your education is really about knowledge of self. You really have to start with helping students understand themselves, including what they want to know and how they can gain the knowledge they seek.

Through that lens, the first thing I would do is implement a method for students to better understand their interests and potential. Then, I would design their learning around that. I think there’s some basics that everyone needs, such as an understanding of numbers and language. After that, the focus should be on their unique interests with an understanding that those interests may change along the way because learning is a journey.