At Avalon School, a public charter school in St. Paul, Minnesota, George sat slouched, rolling a pen back and forth across the table. He is diagnosed with ADHD, autism, dysgraphia, and anxiety. George was six months new to Avalon School, and said he’s still getting used to this “different” place.

George shared that in previous programs, including a juvenile center, people often described him as difficult. Sometimes his mind moved too fast or slow, or it moved in different directions. He didn’t feel heard, would get frustrated, and then might get in trouble. The message he had internalized was that the problem was him, and he did not belong.

George’s story isn’t an outlier. More than 7.5 million public school students receive services under the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA), representing about 15% of all young people. And still, learners with learning differences are nearly three times more likely to drop out, twice as likely to be suspended, and one-third are held back at least one grade.

A Different Kind of Response

Things are different at Avalon School, George said. The reason? It started with soapbox cars.

George builds soapbox cars on the weekends. At Avalon School, instead of sidelining that interest to solely prioritize academics, his advisor, special education teacher, and psychologist listened and leaned in. It didn’t happen overnight, but that understanding became a launch pad to connecting his love of mechanics and design to writing, geometry, and physics with relevance and purpose. He received the specialized services he needed, in and out of school. Just as importantly, his team’s openness and curiosity in him, qualities his mom notices ripples across the Avalon community, opened new doors: exposure to new skills and areas of interest, social connection, and a slow but steady rebuilding of confidence.

Avalon School didn’t create this approach just for George. Avalon is part of a number of learner-centered sites that begin with each young person’s needs and interests, and ground that in a broader culture of relationships, shared responsibility, and relevant, real-world learning.

So why do sites like Avalon’s still feel like exceptions, especially for learners with learning differences?

Despite a growing awareness of learner-centered education, myths about young people with learning differences and what they need continue to persist and shape what’s seen as possible for them. Below are some common myths that educators from across the country have heard in their communities, and some of the approaches we have witnessed in learner-centered sites to help create an environment where all young people can learn in a way that’s suited to them.

Myth 1: Students with learning differences need rigid structures for success.

It’s a well-intentioned belief: the best way to support those who struggle with focus, regulation, or executive functioning is to remove distractions through tighter schedules and firmer rules. The assumption is that a highly controlled environment can prevent young people from falling behind.

Learner-centered sites have a different take. What we’ve observed:

- Responsive, relationship-based structures that cultivate self-advocacy and connection

- Integrated support and accommodations

- De-emphasis on compliance in service of opportunities to cultivate personal and skill development

At Lafayette Big Picture High School in New York (part of the international network of Big Picture Learning schools) “daily routines function as guiding frameworks rather than hard-and-fast rules,” said an advisor. Each day begins with advisories and community meetings—traditions that set the tone through celebrations, team activities, and announcements. Off-site internships typically happen twice a week, and schedules flex around those internships and other learner needs. On-site internships are also available for learners who may need additional support or have interests best suited to on-site exploration, like culinary arts, maple syrup manufacturing, event planning, and woodworking. Otherwise, “we adjust our schedules and physical spaces so every student can work in a way that suits them best… we prioritize relationships, relevance, and rigor in that order.” Though over 45% of learners here qualify for an Individualized Education Program (IEP) or 504 plan, the team doesn’t wait for paperwork to adapt. “A lot of our students don’t even know they have accommodations. They’re so integrated, they just see it as how we do things here.”

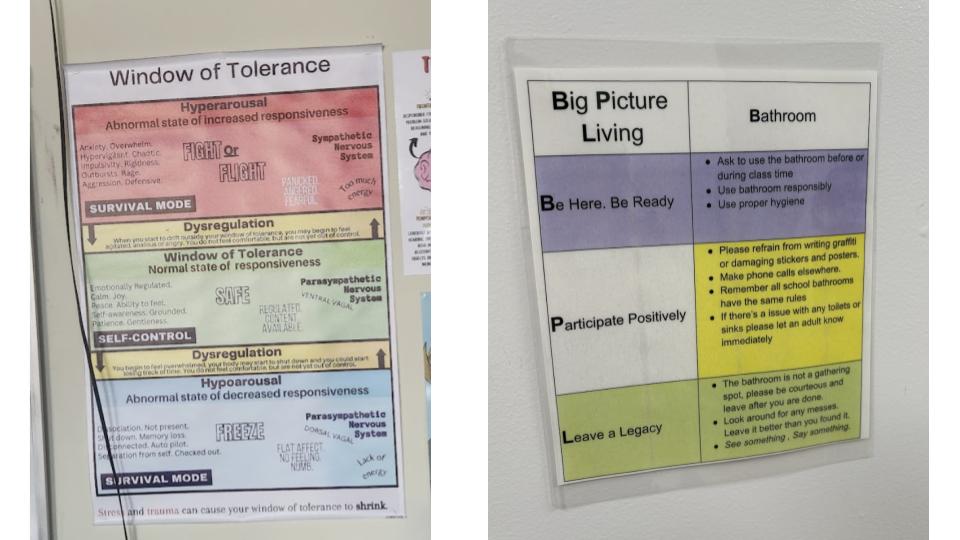

A thousand miles away on an urban farm in Florida, about 30% of Verdi EcoSchool’s learners are diagnosed with learning differences. They also have daily traditions and rhythms to elicit intentional moments of reflection, co-creation of goals and intentions, and connection. Around campus, shared expectations are posted not as static rules, but as evolving community commitments that learners and advisors refer to. “When conflicts arise, learners know to ask their peers to gather at a picnic table in the garden to talk, listen, and repair,” an educator shared.

Structure matters, but it should support young people’s development and needs, not just enforce compliance. That looks like structures that may look firm in some cases and flexible in others.

Myth 2: Students need to be motivated or self-directed to thrive in learner-centered environments.

A common misconception is that learner-centered education only suits certain kinds of young people. The thinking goes: if a young person hasn’t demonstrated internal drive, they will flounder in learner-centered education.

Learner-centered sites have a different take. What we’ve observed:

- A desire to engage young people with various backgrounds, needs, and strengths

- Skills like self-direction, executive functioning, reflection, leadership, and motivation can be developed; they are not prerequisites

- Emphasis on strengths-based, personalized approaches

At Norris School District in Wisconsin, where over 70% of learners could qualify for an IEP, many arrive carrying years of deficit-based messaging—told what they can’t do. “We make decisions based on the person in front of us more than their IEPs and diagnosis,” an educator emphasized. From day one, learners are invited into deep, reflective conversations like: What do you enjoy? When do you feel most and least successful? What triggers you? What works best for you? These insights, voiced by learners themselves, become the foundation for individualized learning plans, projects, and a “Who Am I?” exhibition after 30 days, presenting about how they’re growing, not just academically, but as increasingly self-aware people who are developing the vocabulary to reflect on their strengths, needs, and positive exploration of their futures. Paraprofessionals, called Navigators, also support all learners to explore their interests and skills. While trained to work with young people with learning differences, they expand opportunities by providing support and mentorship for all learners in topics like woodworking, music, and marketing.

At IDEA High School in Washington state, 23% of young people have IEPs, and all learners are supported through a full-inclusion model. Advisors and specialized teams meet learners where they are, viewing mindsets, motivation, and executive functioning as skills to be developed. “Motivation isn’t something you have to conjure yourself because it happens when learning feels connected to you and you’re listened to,” shared a junior. That connection is built from the start. In grades 9–10, learners engage in various hands-on projects (like fisheries management, boat-building, product design, and audio recording) that make learning real and interesting. By grades 11–12, they transition into Next Move internships, where they apply those experiences in professional settings. Throughout, teens gain both professional, life readiness skills (like time management and writing work emails) and relational ones (like reflecting on reciprocity, service, civic identity) both intentionally and organically. IDEA’s Bridge Program reinforces this strengths-based approach by having learners serve as peer supports on topics and skills they enjoy, deepening their understanding while building confidence, empathy, and leadership.

When learning starts with who each young person is, motivation and self-direction aren’t requirements, they’re a result.

Myth 3: Youth with learning differences need more schooling before accessing interesting, real-world learning.

This myth shows up as: “Focus on the basics first.” It’s also often rooted in a belief that real-world or interest-based learning is a reward to be earned, something reserved for students who have “proven themselves.”

Learner-centered sites have a different take. What we’ve observed:

- Relevant, real-world learning is an expectation, not a reward

- Academic and life skills can be built through real-world contexts, not in preparation for them

- Inclusion is designed for, not added on

At the Met High School in Rhode Island, real-world, interest-driven experiences are the foundation rather than the end goal. Every learner is expected to engage in internships throughout high school. These experiences aren’t separate from academic learning; they are the context in which academic skills are built. As one educator explained, “reading, planning, and time management are learned in context, like prepping for a mentor meeting or doing research for a project.” For a young person with dyslexia or one who’s struggling with reading comprehension, this might look like working with an advisor to decode technical terms and text from their internship field, turning what could be a barrier into a bridge. At the Met, young people aren’t asked to prove they’re ready for the real world—the real world is part of how they get ready.

At World Ocean School in Massachusetts, learning happens aboard a tall ship, sometimes for weeks at sea, where daily life and academics are fully integrated. Instead of bell schedules and worksheets, learners engage with the rhythms and responsibilities of life on the water. “We have many learners with diagnoses join… I have seen a watch group consisting of a nonverbal student with autism, a student with dyslexia, a student with ADHD, and a couple of students with no learning differences live and work together for two weeks aboard the ship,” said a crew member. They were able to find success because of shared goals around caring for each other and the ship, respect, verbal and visual support, and personalized plans co-created with families, learners, and learning specialists that align academic, life, and mental wellness goals and accommodations. Whether mastering physics through navigation, writing reflections on the power of nature, or gaining patience and empathy by practicing communication in tight living quarters, there’s something to learn in every moment. “Students who struggle in the classroom often come on board and find that the ship’s environment is one where they can thrive” because of peer-to-peer support, dynamic, hands-on learning, and the sense of belonging and trust that’s fostered amongst learners and crew members on the boat.

Real-world learning isn’t something to wait for. It’s an inclusive and foundational way to support learners to develop mindsets and skills with relevance.

Perhaps Learning Differences Are Not the Exception, They Are the Starting Point

What we observed is by no means a silver bullet. George said he still has bad days. Educators have shared how this work can be messy and complex. But the learner-centered sites we visited didn’t ask if young people with learning differences could thrive. They ask themselves how they can ensure it, and take action.

These sites have:

- Stopped treating learning differences as edge cases.

- Assumed and embraced neurodiversity and learning variance from the beginning.

- Redefined structure around connection and personal development, not control.

- Designed sites and accommodations with the whole learner in mind, not just the ones with paperwork.

- Made relationships and purpose batteries for joy and growth.

My invitation to you: Identify one practice in your learning community (like a schedule, advisory system, assessments, real-world learning opportunity) and ask: Who thrives in this structure? Who struggles? Why?

I would love to hear your reflections about what you have found works!

This blog is part of a project supported by Oak Foundation. The project explored learning differences in learner-centered environments, highlighting inclusive practices, learner outcomes, and conditions that support all young people to thrive. For privacy, the names of learners have been changed.