Distinguishing Learner-Centered Ecosystems: A Move from Disconnected to Cohesive

Note from Education Reimagined 24 August 2022

By Kelly Young

By creating these connections, skill and competency development are acknowledged and credentialed across the ecosystem, empowering the learner to show and clearly communicate what they can do and know — breaking down the barrier between formal and informal learning.

Kelly Young

Over the past couple of months, we’ve been discussing The Big Idea with partners, families, and learner-centered colleagues. One thing has become clear — distinguishing between the conventional public K-12 education system; learner-centered ecosystems; and other kinds of networked systems, such as community schools, is necessary if we are to make visible what makes the pursuit of equitable, learner-centered, community-based ecosystems unique and worthwhile.

We’ve been learning from organizations and partners like KP Catalysts and B-Unbound, who have helped us refine how we see and talk about the differences. While fully expressed learner-centered ecosystems do not yet exist in their entirety, countless leaders have been working towards similar visions for decades and are a rich source for lessons learned, challenges to look out for, and allies in this effort.

In this exploration, it has also become increasingly clear that the vision of learner-centered ecosystems can be easily collapsed with efforts that, in their own ways, seek to break down or circumnavigate the silos that exist between K-12 education, the youth development sector, and communities and families.

As with all of Education Reimagined’s work, we want to be careful to avoid this collapsing of terms, ideas, and visions. This isn’t because one vision or effort is better than the other nor are we just worrying about semantics for the sake of it. Rather, it is because these efforts and approaches are different in significant ways and those differences have a direct impact on the work to be done, the challenges faced, and the conditions necessary for their thriving.

Today, I am eager to share our latest thinking about the distinct structure of an ecosystem and the impact this distinctness will have on this field’s work moving forward. I’m sharing this not because we have it all figured out — we don’t — but rather, because in our collective search for how to advance ecosystem invention, I want to invite new conversation, thinking, and insight from this movement of learner-centered leaders. In fact, in what I’m sharing below, you’ll see some of my own back-of-the-napkin sketches; we are deep in this exploration, don’t assume to have all the answers, and are eager to hear feedback from you.

Okay. Let’s start by going to the far ends of the continuum — from what we typically see in conventional models to what we envision as being possible in thriving, learner-centered ecosystems.

Disconnected — The Conventional Design & Approach of K-12 Public Education

The current conventional system of education is largely disconnected from outside experiences and partners. Of course, educators make meaningful connections when and where they can, take learners on site visits, and do their best to bring mentors into the fold. However, this is largely up to the individual educator or school site to facilitate and, as such, happens only sparingly.

Those experiences that young people do get outside of school are largely dependent on a parent or guardian making a connection, being available, or paying for an experience, resulting in largely inequitable opportunities. Providers and partners that engage learners in opportunities outside of a typical school day have little to no connection to educators within the classroom. If they do, the interactions are transactional and minimal at best, resulting in a largely disconnected journey of learning for the child.

Further, these experiences outside of school — whether they are with an organization or are just valuable learning, like learning to play the drums with a mentor or neighbor — are not recognized in the formal record of learning for the learner. So, while a learner may have extensive and varied experiences through which they’ve built diverse competencies, including those experiences they have with family and in their homes, none of that is automatically visible once they enter the classroom. Again, many educators make special effort to discover and learn about a child’s out-of-school life but it is on their shoulders to go “above and beyond” to do so with almost no ability to credential such experiences.

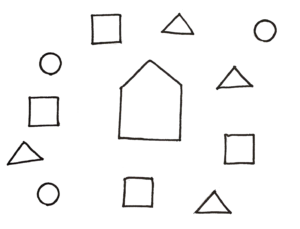

Conventional K-12 Education System — Disconnected

In the above sketch, I’ve tried to capture this disconnected approach — it shows the school building (or district) at the center of a diverse community, full of other assets, organizations, people, and places in which children can and are learning. But, each of those places, including the school, stand alone — with no institutionalized infrastructure in place to form connections or build streams of communication. This is the design of our education system, built in the Industrial Era, when the idea of building a connected, interlocking system of public education was not even on the table and long before many of the technological assets that would make it possible existed.

Connected — Learner-Centered, Community-Based Ecosystems

Now to the other side of the spectrum. Whereas the current public education system’s very structure is designed to consolidate and coordinate all credentialed learning into one building with one set of adults, a learner-centered ecosystem is structured to create an interconnected web of learning experiences and opportunities, enabling each child to pursue their own unique learning journey grounded in community. A learning journey characterized by the five elements of learner-centered education and supported by reimagined structures of accountability, governance, funding, transportation, assessment, and personnel systems.

This is a “connected” approach — in pretty much every sense of the word.

In an ecosystem, myriad spaces of learning (what we are calling home bases, learning hubs, and field sites) speak to one another and create a continuum of learning experiences that meet the learners’ needs and goals. Already existing assets in the community, such as arts centers, museums, businesses, parks, playgrounds, civic centers, shopping malls, and theaters, would be leveraged as resources and valid (even prized) places of learning.

By creating these connections, skill and competency development are acknowledged and credentialed across the ecosystem, empowering the learner to show and clearly communicate what they can do and know — breaking down the barrier between formal and informal learning.

Moreover, rather than needing to piece things together on their own, families are supported to chart a course and navigate an ecosystem’s varied offerings for their child with professional educators in the system serving as advisors to the child to ongoingly reflect and course correct as needed. And, although the consistency of staying in a single school building all day may be reduced (particularly for older learners), structures would be in place to ensure custodial care, transportation, and safety, so that families could count on their children’s wellbeing and health to be prioritized. New policies and financial structures would ensure the system is equitable and adaptable to the needs of learners, their families, and the community.

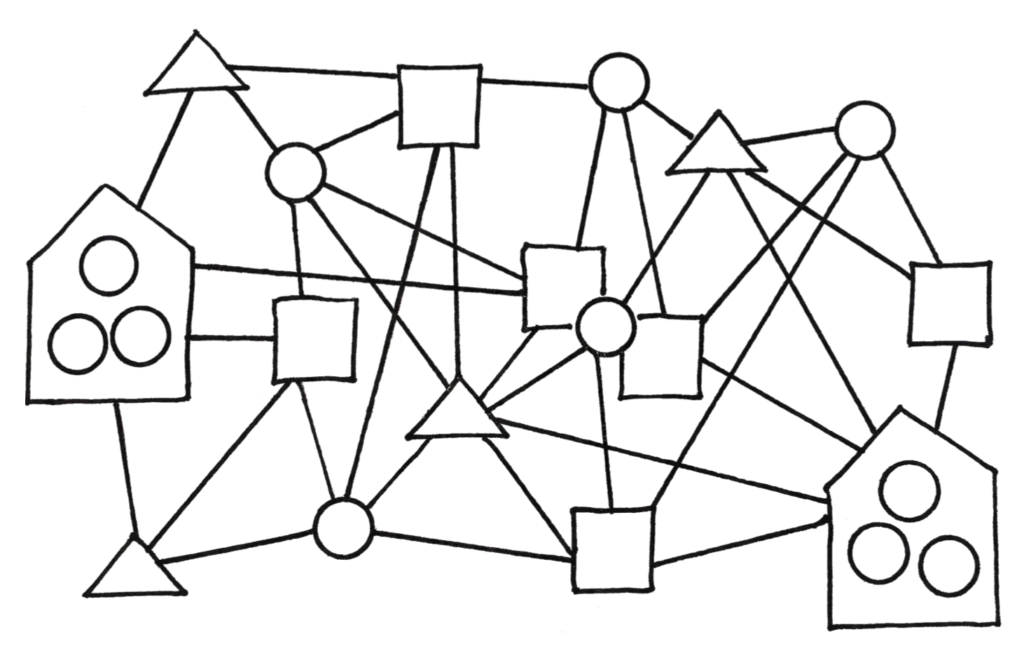

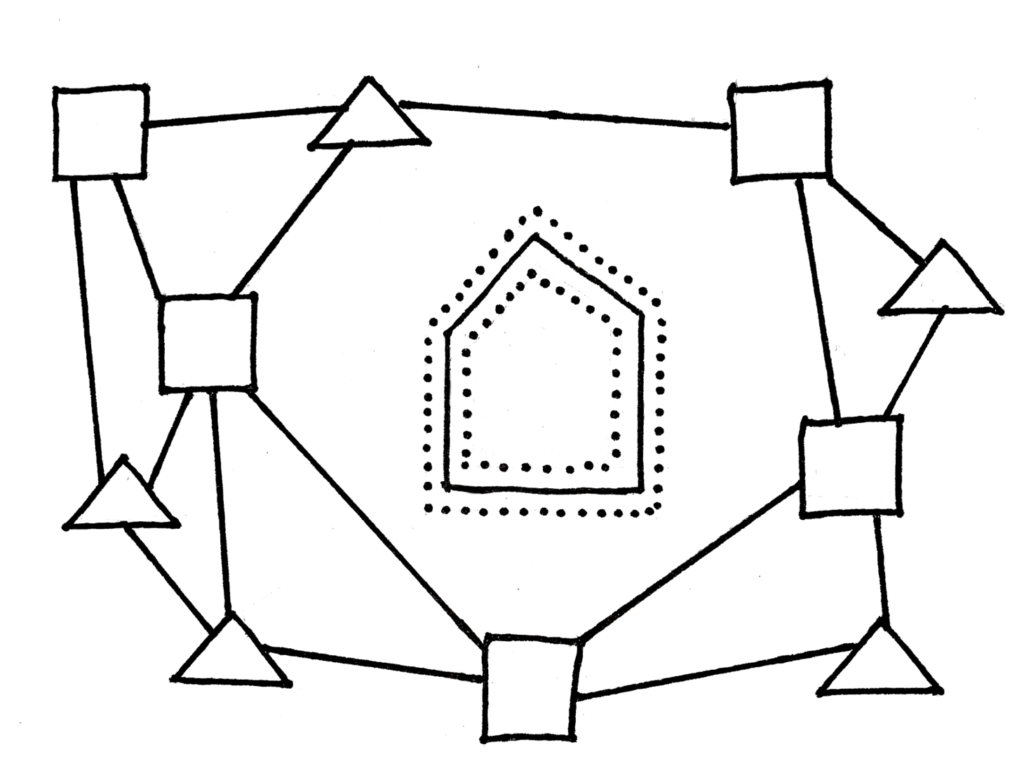

Equitable, Community-Based, Learner-Centered Ecosystem — Connected

In the above sketch, I’ve tried to capture that connected web of learning experiences that would comprise a dynamic, thriving learner-centered ecosystem. While it may look complicated, we prefer to think about it as being complex — something capable of living up to the challenge of serving each and every child in the community equitably and powerfully. And, it is important to remember this is a matter of shifting and inventing new infrastructure. It is not assuming we could tweak or adjust the current education system’s way of operating just enough to make room for some version of this learner-centered ecosystem. It is about envisioning and together, bringing to life what the new ways of organizing, supporting, and credentialing learning could look like for a whole community.

Now, these images of a disconnected public education system versus a connected learner-centered ecosystem are relatively straightforward. It is in between these two ends of the spectrum where we are finding the most learning can be done — both for the insight they can provide into how we can create and support fully expressed learner-centered ecosystems and for the “why” it is worth pursuing such invention in the first place.

Connected But Outside — Connected Learning Systems of Out-of-School Learning Providers

As Karen Pittman, Senior Advisor to Education Reimagined and Founder and Partner of KP Catalysts, reflected in a piece published a few weeks ago, we can look across the country to find community learning systems — from “national brands, like the Boys and Girls Clubs and Ys; local networks, like the Providence Afterschool Alliance and other intermediaries in the Every Hour Counts Network; or those local, regional, and national organizations focused on topics, such as STEM, the arts, or civic engagement.”

These community learning systems have found ways to build connection, integration, and communication between out-of-school, after-school, and youth development providers to support a more robust learning experience for their young people. In many cases, these are networks providing youth with learning that is more relevant and culturally responsive than they are finding in their school environments. Likewise, youth are choosing to come back day after day to these experiences because they are meeting them where they are, whether that means aligning with their interests, validating their lived experiences, or providing them with supportive peer groups and adult mentors.

Yet, these networks rarely connect deeply with the school system and when they do, it does not translate to fully acknowledging or credentialing the skill and competency development happening for these young people. It remains an extra, nice to have program but not seen by the conventional system as a pivotal development opportunity. In this structure, the school or school system remain central and untouched; the learning and educating that happens within the school day is not transformed, no matter how learner-centered the out-of-school experiences may be.

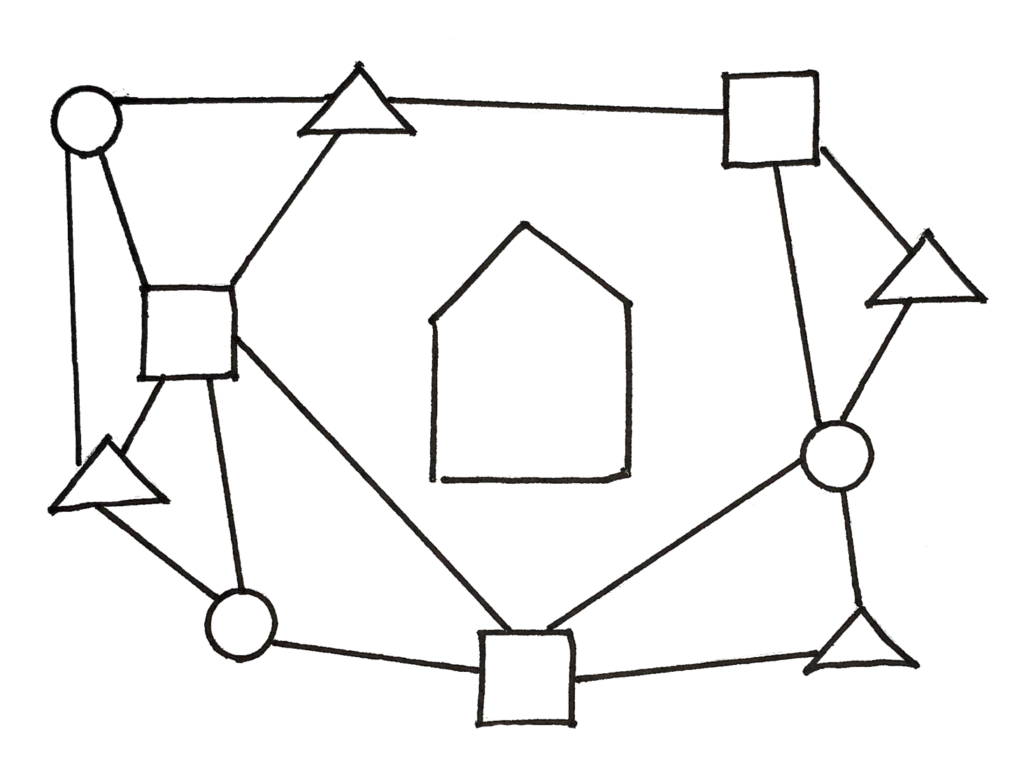

Community Learning Systems — Connected But Outside

In the above sketch, we can see the networking of varied extracurricular or youth development programs and opportunities, while the school or school district remains disconnected but central.

Examples of these sorts of connected learning systems, as Karen calls them, abound with learnings and insights that can inform and support the invention of learner-centered ecosystems. They’ve had to answer such vital questions as: How do you create connections across programs with varied purposes, audiences, funding models, and curriculum? What role must a coordinating entity play to ensure clarity of communication and quality of service? How do you attract and retain our most vulnerable learners’ enrollment in non-compulsory learning opportunities?

Yet, despite all they’ve demonstrated, the learning that happens in these environments remains largely unacknowledged by the conventional education system, limiting a young person’s ability to communicate and prove what they can do to an employer, college admissions officer, or family member. There is also a real challenge in ensuring equity of access and support; it can be difficult for young people to find and participate in such programs unless they have an adult who can do the research, coordinate the transportation, and in some cases, pay for the offering. Moreover, continuing to operate outside of the school’s periphery, the struggle to maintain the funding and staffing to stay open is very real for these programs.

A learner-centered ecosystem approach offers the opportunity to address these challenges while continuing to leverage all that these connected community learning systems provide when it comes to powerfully serving youth.

Connected but Unintegrated — Wraparound Services to Support Schools

In recognizing the need to attend to more than just academics, schools across the country have connected with community partners to build wraparound services to meet young people’s physical, mental, and wellbeing needs in varied ways. These efforts are intended to remove the barriers to learning that many of our young people face, whether that is hunger, unmet physical or mental health needs, lack of stable housing, or issues of abuse or neglect.

Acknowledging a single educator or even a single school cannot be responsible for addressing all that a child will face, these community schools, as they are often called, seek to bring in and supplement their efforts with partners and organizations located in the community, as well as creating more coherent opportunities for family engagement and support.

What this structure does not do, however, is relinquish the centrality of the school building as the place of learning nor shift the focus away from a narrow one of academic success.

It brings some of the essential community resources into the school but still often leaves untouched the opportunities that exist outside of that building to influence how and where learning happens. There are valid reasons for this in the current system’s structure, including challenges of transportation, accountability, and safety. Bringing the community “in” ensures the school can still address these things for the youth it serves.

In other cases, this wraparound service approach may be taken by schools and districts located in communities that also have integrated, connected out-of-school networks. But, while this gets closer to a vision of an ecosystem, it still maintains that separation between the formal school day and the rest of a child’s life — keeping the “out-of-school” opportunities uncredentialed and centralizing the authority of the school system for all academic matters. Again, it does not change how learning happens when learners are in the school building.

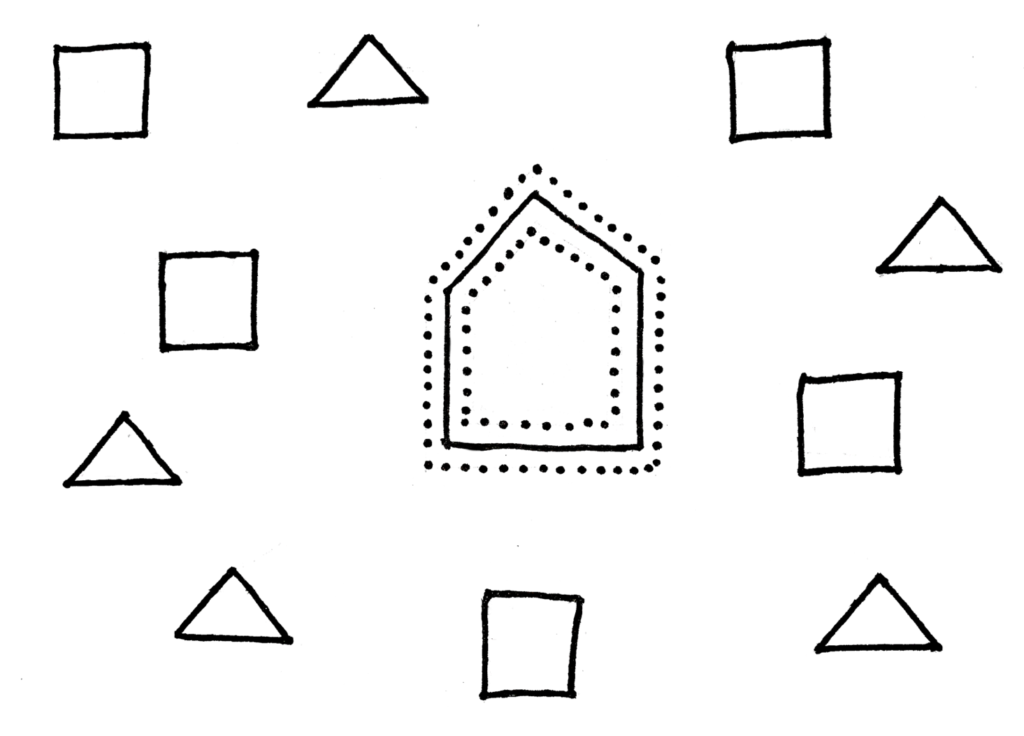

In the below sketches, I’ve captured these two versions of how we’ve seen this play out.

Wraparound Services in a K-12 school with disconnected out-of-school/afterschool offerings.

Wraparound Services in a K-12 School in a community with a connected learning system of out-of-school/afterschool offerings.

Both of these iterations seek to acknowledge that education is trying to support a whole, full human being to grow and develop. However, they both keep school as a construct in place in a way that continues to exclude the vibrancy of the community and maintain that academic, knowledge-based learning must be the primary focus of a child’s education. Rather than inventing newly how a system could support the growth and development of full human beings, they seek to modify and bend the current system.

A learner-centered ecosystem approach takes on the challenge of that new invention — and, as I’ve said before, although daunting and certainly challenging, this invention offers the possibility of a system that intentionally and integratedly supports youth to build, navigate, and make sense of unique learning journeys in the context of community.

When considering this proposition of invention, I often look to a quote by Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr.: “I would not give a fig for the simplicity this side of complexity, but I would give my life for the simplicity on the other side of complexity.”

I see how that has played out in the many, many, many ways we, as a nation, have tried to morph and change our current system to meet our goal of serving youth equitably and powerfully — creating more and more complexity. Yet, in each conversation about what a learner-centered ecosystem could look like and how it might operate, I can just about see it — that level of “simplicity,” of having a system that is in integrity with its purpose. I believe there is simplicity on the other side of complexity when it comes to education and believe it lies in the invention of learner-centered ecosystems.

What do you think? What can we learn from all that has been done before today to find that simplicity on the other side of complexity? If you or your organization see possibilities for ecosystems in your community, reach out and let’s talk.

New resources and news on The Big Idea!

×

We recently announced a new R&D acceleration initiative to connect and support local communities ready to bring public, equitable, learner-centered ecosystems to life.