The Paradigm Shift: This is What Happens When You Grow Up in a Learner-Centered Family

Insights 21 December 2017

By Ulcca Joshi Hansen, Education Reimagined

At Education Reimagined, we are always discussing the importance of collecting stories from education stakeholders who have experienced an “ah-ha” moment when the paradigm shift from school-centered to learner-centered education happened for them. Together, we can expose the unique roads we’ve traveled and unearth what is common amongst them all.

To continue our intention to collect these stories en masse, Education Reimagined’s Ulcca Joshi Hansen will be sharing her personal story where the idea of learner-centeredness was something she was born into rather than a shift experienced later in life.

Want to share your story? Let us know!

This is a movement whose time has come.

Ulcca Joshi Hansen

Associate Director of National Outreach and Community Building, Education Reimagined

IN SOME WAYS, MY JOURNEY TO LEARNER-CENTERED EDUCATION STARTED BEFORE I WAS BORN. My parents immigrated from East Africa, and brought with them a non-western view of the world. While they were both born and raised in Tanzania, my grandparents hailed from western India, part of a large migration during British colonial rule.

The Indian presence in numerous east African countries birthed a unique culture that blends elements of Indian and native African cultures and language that seeped even into their speech, English sprinkled with hints of Swahili and Gujarati.

When I was born, I was immediately buffered from the strong post-Enlightenment, western paradigm that has sustained school-centered education in the United States for more than a century. This buffering was all the more present when, during my earliest years, I went to live with family in Arusha, Tanzania.

The mother tongue of my childhood home was rooted in Sanskrit, the tongue of eastern poets and mystics; a language that carries within it distinctions, emotions, and concepts not readily translatable within modern western languages. I didn’t learn English until I returned to the US to begin school. It makes for an interesting exercise to reflect on the ways in which language shapes how the brain accesses and makes sense of the world, but I digress.

The fusion of western thought with my family’s eastern roots was unmistakable. One need not explore any further than the bookshelves in our Millington, NJ home. American classics and a leather-bound Encyclopedia Britannica set (a must-have purchase for many South Asian immigrant families of that era) were proudly displayed. Yet, nestled among these western classics were books of poetry and philosophy by Rabindranath Tagore and Jiddu Krishnamurti. There were stories of the Bhagavad Gita, the Vedas, the Buddha; thick books on Indian philosophy.

These stories and traditions came to life when relatives and friends came to visit. Sometimes there were evenings of chanted prayers and songs, words like those of the Gayatrimantra that felt awkward in my mouth:

om bhūrbhuvaḥ svaḥ tatsaviturvareṇyaṃ bhargodevasya dhīmahi dhiyo yo naḥ pracodayāt.

They offered tantalizing wisps of ideas: interconnectedness, interdependency, the unity of existence, and the illusion of separation from oneself and others.

It took me years to appreciate how some of the things that made me embarrassed among my peers growing up were actually reflective of a much more socially- and ontologically-advanced ethic than what the American world held up as “normal” and “better.” Things that were “weird” during childhood—eating vegetarian, re-using, up-cycling, and consignment—are now all the rage.

America’s emerging acknowledgment that environmentalism, conservation, and ecological justice matter because human beings are not separate from the world has been my “normal” since birth.

The same goes for practices such as yoga, mindfulness, and meditation. These are activities grounded in a belief that process is primary and that knowledge and mastery unfold from it; they sit in tension with Industrial Era ideals of linearity, efficiency, and easily quantifiable data.

They are ways of being that are about a slowed down and expanded awareness of time, totally at odds with campaigns and devices that reel us into the illusion that it is possible or desirable for us to maximize the productivity of each minute of our day, making a time-bound notion of efficiency our master.

Reconciliation: Balancing My Eastern Experiences within the Context of a Western World

Like many immigrants, my parents learned to navigate the American school system without the benefit or baggage of prior experience. Their personal educational trajectories did not overlay neatly on the standard kindergarten through twelfth grade pipeline.

My parents had experienced formal schooling, though neither had gone to college. They had acquired an enormous amount of their knowledge and skills through work and practical experiences. So, while they instilled in my brother and me a level of deference and respect for schools and teachers, they held a flexibility in their understanding of when and how learning happened. This flexibility played out in numerous ways for me as I grew up.

My parents supported my foray into a wide range of activities—community theater and acting; poetry and playwriting; martial arts; study abroad programs that took me to Russia, France, and eventually to Germany for my entire senior year of high school. My father pushed me to talk to my teachers and school administrators about getting “credit” for what came out of these experiences—the plays I wrote for state competitions; travel journals and reflections on cultural differences; papers on the political upheaval that was roiling eastern Europe in the early 1990s. My parents instilled in me the idea that learning happens all the time.

Because these ideas were becoming conscious for me at the same time I was studying education and learning to be a teacher, I realized the approach I wanted to take as an educator was in tension with what I was being taught and what I was seeing happen in schools.

Ulcca Joshi Hansen

Associate Director of National Outreach and Community Building, Education Reimagined

Even so, I happily and fairly easily excelled in the game of school. But, I’d be remiss not to mention an important variable that led to my academic and personal growth as a child, one that is much harder to find in today’s education system due to factors like high teacher turnover.

I was given the freedom to explore myriad topics of interest under the experienced and watchful eyes of many teachers who had collectively seen thousands of students grow and learn. My teachers’ experiences enabled them to embrace the “normal” variation that exists in the growth, interests, capabilities, and challenges of young human beings.

Their wisdom coupled with the much needed time to make school a full set of experiences (e.g. play, recess, art, music, open-ended conversations, space for the social dramas of childhood and adolescence to unfold) made my experience in traditional school far more learner-centered than what can be found today.

As early as middle school, I was intrigued by western concepts that seemed to reflect the mysticism of the eastern ideas I was beginning to explore more consciously. Lucky for me, my middle school teacher, Mrs. Olinger, was willing to let me research and write about seemingly random topics, like extrasensory perception, astrology, astral projection, and ghosts.

She trusted my forays into these topics would eventually lead me somewhere meaningful, and with her guidance, they did. How many learners in today’s school-centered system are able to explore such non-standard subjects?

My interests evolved into wanting to understand what we knew about the human brain and its capabilities; questions of consciousness and what it meant to be a person; the history of witchcraft; and the social implications of the tensions that emerged between pagan, mystical, and native cultures and the rise of organized Christianity in the US and Europe.

Throughout middle and high school, I used every open-ended writing assignment to thread together a study of the unusual: fractals; chaos theory; post-traumatic stress disorder and its impact on the body and learning.

The scientists and writers I found most compelling were, at the time, slightly off the beaten path. They framed things in ways that pointed to the interdisciplinary nature of ideas—so different than the way classes and school were structured.

Some teachers found it hard to understand the connections between the ideas I was exploring. But, I found it strange that school kept wanting to separate things out in ways that seemed to miss obvious and important connections. I had the niggling sense that these separations often led us to focus on the wrong questions or miss potential explanations. This sense grew as I embarked on post-secondary pursuits.

Reconciliation Overload: Returning to My Roots for Deeper Understanding

It’s probably not surprising that in college, I gravitated towards the study of philosophy, in addition to training as a teacher. I felt constrained by my department’s focus on analytic philosophy, a British school of philosophy deeply embedded in formal logic, conceptual analysis, and mathematical principles.

To simplify, for the sake of comparison, the analytic tradition strives to understand the world by considering individual pieces, believing that to try and understand ideas in total relationship to one another is far too complex a task for the human mind. This flew in the face of my gut instinct, which was that things are interconnected and that the arguments we were having in class had absolutely no value in the real world where it is impossible to disconnect things from each other.

Needing to break away from this narrow lens of the world, I established a set of independent studies for myself that would allow me to travel to India for a summer to take a self-designed course on Indian philosophy and religion.

While delving into Hinduism, something critical clicked for me. What the post-Enlightenment, western tradition perceived as polytheistic was actually monotheistic in the sense that it seeks to describe a unified ultimate reality, of which there are infinite manifestations.

This was the same notion of reality that had been described by ancient and medieval philosophers and mystics in the west and is at the heart of many eastern traditions and most indigenous cultures throughout the world. But, the idea that One ultimate reality can encompass every possible distinction within itself was something that the prevailing paradigm of modern, western analytic thinking found nearly impossible to accept.

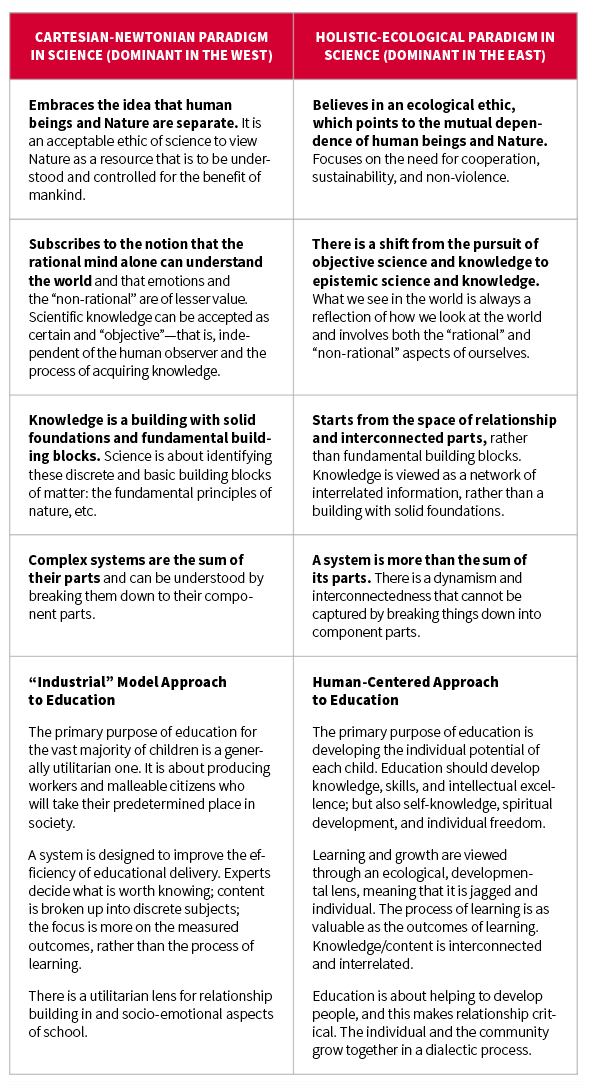

I wanted to understand the roots of this paradigmatic divide in the world, and I was, even then, beginning to see the implications these two views of the world had on debates within education. My philosophical gears start churning when I bring this idea of paradigms up, so to make it more digestible, I’ve laid out the two paradigms in the following table:

Because these ideas were becoming conscious for me at the same time I was studying education and learning to be a teacher, I realized the approach I wanted to take as an educator was in tension with what I was being taught and what I was seeing happen in schools.

The pendulum between the two paradigms and their corresponding educational approaches has been swinging in America since the late-1800s. The progressive movements of the 1960s and 1970s had launched the teachers who taught me, which explains why their approach to education felt more human-centered, both as a student and as a young teacher. However, I was coming into the profession at a time when the pendulum had swung against what some people saw as too much “looseness” in the public system.

There was an increased emphasis on “the basics,” the worshipping of “objective” measurements of student progress and outcomes, and a belief that the “right” structures, systems, programs, and curriculum could right the ship. This didn’t sit well with me, in addition to not aligning with what I knew about human beings and learning.

I went on to spend years in graduate school understanding the emergence of what people today talk about as the “industrial” model of education, which I have come to believe is too narrow a lens—a topic for a whole separate article.

Reconciliation Over: The Time Has Come to Transform Education

Suffice it to say that it has been a tenuous 15-20 years thinking and talking about ideas that have felt so counter to the predominant debates and discourse within education circles. So many other arenas of our lives have been totally transformed by the shift to an holistic/ecological paradigm over the last fifty years—the digital world would not exist without a shift away from the Cartesian-Newtonian paradigm nor would the fields of ecology, nanotechnology, and systems theory to name just a few. Yet, the prevailing minds in our public education system have been unable to see beyond the old paradigm.

Here’s the good news. History tells us it’s not uncommon for the social and educational spheres to lag behind the scientific. And, there are many indications that we have arrived at a moment when the values that undergird holistic, human-centered education may be able to disrupt the architecture of America’s public education system for good.

First, these ideas have always gained traction at moments of social, economic, and political unrest. This tends to occur, in part, because people are more willing to look to education as something that can be socially transformative and not just utilitarian.

Moreover, everything mainstream science has confirmed about human growth and development—how the brain works, how human development happens, what learning really looks like—reflects what human-centered education has always asserted and sought to build from.

And, most promising to me is that unlike any other moment in modern human history, the world demands what learner-centered education produces. The idea that we wanted to develop human differences, that education should be about human fulfillment and freedom, that mutuality and interdependence needed to be understood and valued—these have always been deeply counter-cultural. No longer.

In a rapidly changing environment, we need to nurture human difference in order to adapt to changes we cannot predict. In a world of machine learning and artificial intelligence, we need individuals who possess deeply human capabilities like adaptability, empathy, compassion, authenticity, and human connection. And, most of all, the world needs human beings who accept that their individual well-being and the well-being of their fellow neighbor and the ecological collective are intertwined. This is a movement whose time has come.

New resources and news on The Big Idea!

×

We recently announced a new R&D acceleration initiative to connect and support local communities ready to bring public, equitable, learner-centered ecosystems to life.