Preparing Young Learners for Life Beyond the Fourth Industrial Revolution

Voices from the Field 23 October 2018

By Stephan Turnipseed, Pitsco Education

How do we use education technology to enhance learning when the technology itself is outpacing our ability to deploy it in education?

Stephan Turnipseed

Executive Vice President and Chief Strategy Officer

Every day, we discover bloggers and pundits crying for an end to education as we know it, favoring their version of what will prepare children for the fourth industrial revolution. Having been born in the second, fully experiencing the third, still working into the fourth, and planning to be around for the fast-approaching fifth and sixth waves of industrial revolutions, I find this position—thinking one revolution ahead—far too limiting.

The future of education has nothing to do with preparing children for industrial and technological trends. We must prepare children to be uniquely human in an increasingly unhuman (and occasionally inhuman) world. A 2018 PricewaterhouseCoopers study estimates that by the early 2030s, 38% of jobs held currently by US workers will be automated. And, there is no consensus on what people will do when faced with this reality. Our economic and social systems might not be prepared for this transformation, but one thing is certain—today’s children must be empowered to grapple with this dilemma as adults.

Children must learn empathy, socialization, and the oft-cited life skills of creativity, critical thinking, problem-solving, communication, and collaboration. Education technology (devices, computers, software, and pedagogy associated with these tools) must be utilized to create an experience that enables children to acquire the knowledge, skills, and dispositions for life, not just for the next industrial revolution. Considering this collective need, how should instruction be carried out, and what role should technology play in our world of instant access?

We Don’t Need to Predict the Future, We Need to Let Children Create It

I am often confronted with people stating that kids today are smarter than they were in my day—when education technology was a filmstrip projector. My observation of today’s children is not that they are smarter, rather that they are more connected and therefore able to bring to bear resources previously unavailable.

Education during the second industrial revolution was essentially the acquisition of content that individuals could leverage to create value for society. Entry into the third industrial revolution, which occurred around 1969, was much heralded as fundamentally changing this landscape of learning. However, the facts remain remarkably disappointing as achievement on the National Assessment of Education Performance (NAEP) has been flat throughout the past 45 years.

I recall my personal entry into that world. In the eighth grade, I completed a science fair project around Boolean algebra by creating a one-line computer using switches from an old Trailways bus, a light from one of our farm tractors, and a hand-crank generator from an early telephone. It was a heady time for this 14-year-old learner. I was creating education technology that was a harbinger not only of the future economy but also of my career as an engineer.

In today’s world, one is confounded by the rate of change that Ray Kurzweil states is accelerating to a pace 1,000 times that experienced in the 20th century. How do we use education technology to enhance learning when the technology itself is outpacing our ability to deploy it in education?

Schools must become the garages and farms of the future, where access to a wide array of physical and digital tools is the rule rather than the exception.

Stephan Turnipseed

Executive Vice President and Chief Strategy Officer

In a sense, schools are competing for mindshare of a child. The traditional setting has an outmoded ability to introduce technology compared to the environment the child lives in outside of school. The shortsightedness of preparing children for the fourth industrial revolution is akin to teaching them how to make fire in the face of clickable gas lighters. What is needed is to shape children’s experiences such that they focus on how to acquire and apply knowledge, not just possess it. This is contrary to the notion that we open a child’s head and pour in knowledge. Each child must individually make sense of the world. That is, we can give children experiences but not knowledge. They must personally create the knowledge.

Such was the case with my one-line computer. I have utilized the knowledge I created from that experience to drive my life forward over the past 50-plus years. At every milestone in my life journey, that one-line computer has been my companion. It was present during my time in the military when I learned about the first digital controllers repairing aircraft electronics. It was present when I earned my degree in electrical engineering and worked with graduate students on the first heuristic speech module for a computer. It was present with my design and creation of a small 8080-based computer used to automate pricing, with the introduction of computer data acquisition in the oil industry using a DEC PDP-11, when using early IBM PCs to automate financial tracking of assets depreciation, when LEGO® Mindstorms® RCX was introduced, and when securing patents for the TETRIX® building system. All along my path, my one-line computer has been my companion and remains so today.

This is the mark of how education technology will impact children in the future—not in using it but in creating it.

We must approach education technology and learning as a set of parallel creation processes. To keep pace, the experiences we give children should focus on their passions. We need to provide them with the tools to create, rather than relying on a futile attempt to stay ahead of the obsolescence curves of emerging technology.

Technology Presents a New Opportunity to Transform Education

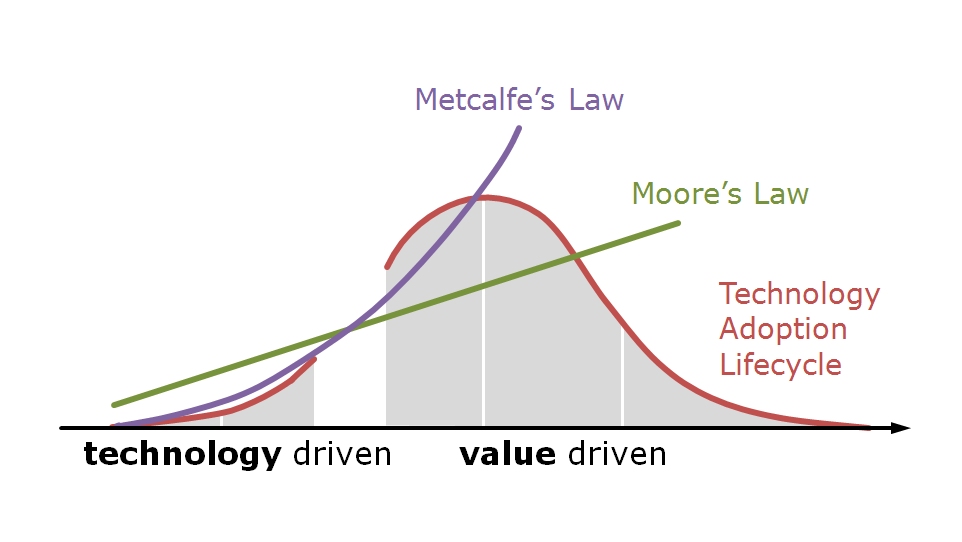

For current and future generations, education must evolve into a networked, communicative phenomenon, rather than the homogenized, rote experience of the past. In this manner, the shift will move from an education technology cycle driven by Moore’s Law to a learning model derivative of Metcalfe’s Law, where the value of the network is the square of the number of connections. This shift happens along the chasm of mass adoption, which can be explored in-depth here and seen in the graphic below.

“And finally, in an unprecedented apotheosis, by combining the three preceding charts and by ― I have to admit ― visually cheating with axes, scales, and representations I came to the observation that the chasm is actually the point where the transition from a technology driven business to a value driven business needs to take place ― and if this doesn’t happen, that any new product or technology introduction is doomed to fail.” Photo and Quote Credit: Marc Jadoul at https://b2bstorytelling.wordpress.com/

This fundamental shift in learning is possible only through the remarkable access achieved with the Internet and global connectivity. There is, however, a possible dark side to this, as access to these assets is not equitable. This inequity is being deepened by the digital divide spoken about in the almost prescient work of Stan Davis and Jim Botkin in The Monster Under the Bed, which was published in 1995.

While there has been much hand-wringing and lamentation of a dystopian future because of this digital divide, I believe there is a way to a much brighter future. Our goal now is to cease the escalating technology consumerism and create a segment of commercial technology that fits a more elegant approach around helping children create the technology themselves—entering the value-driven business approach shown in the graphic above. This type of learning is possible today in a reimagined, student-centric model of education. Of course, this is not a new idea. It is merely an idea that has come of age.

In this brave new world, children are equipped with a love of learning and the tools to make sense of the world though experiences that are collaborative, creative, and richly communicative. The elements of this approach are built around three fundamental ideas—mindsets, toolsets, and skill sets.

Mindsets

Through the recognition that failure is the best teacher, we must provide a safe environment for children to experiment and fail early and often on the path to success. Only in this manner will they begin to appreciate the truth of Edison’s words, “I have not failed. I’ve just found 10,000 ways that won’t work.” This enables students to see that failure is not some value-laden word of despair, derivative of the current test-and-punish culture. Rather, they will see it as an opportunistic stop along the path to success. It is through this process of failure-driven success that children will develop the mindset needed to confidently face the challenges of the future.

Toolsets

If we are to fully take on this mindset, children must be given the tools to experience failure and create success through access to a rich and vibrant tapestry of learning assets and choices. Learning must become more personalized, relevant, and contextualized. Children born in the second industrial revolution, as I was, were afforded significantly more access to a rich environment of tools in garages and on farms. These were places where we could create and revel in the joy of newfound abilities using the tools of the day. These garages and farms were the makerspaces of that generation. Schools must become the garages and farms of the future, where access to a wide array of physical and digital tools is the rule rather than the exception.

Skill Sets

Skill sets are cultivated through practice and the mentoring of adaptive educators. In a facilitative and mentoring role, educators become curators of a child’s interactions with learning from peers, industry, and civil society. They socially embed the child in a relevant and authentic ecosystem of relationships. Education technology becomes an artifact while the community becomes a library of opportunities from which students select experiences that foster the acquisition of skills needed to follow their passions.

The mindset, toolset, and skill set afforded me through my one-line computer are in fact attainable today in collaborative, learner-centered, hands-on STEM labs where failure adds as much, if not more, as success does to the young person’s journey. For example, this creativity-nurturing environment can be found in all middle schools of Placentia-Yorba Linda USD in southern California. Young learners discover their personal interests and aptitudes in the middle-level labs before eventually deciding whether to attend a specific Career Link Academy in high school.

In order to yield positive outcomes for young people and their collective future, we need to prepare them for the unpredictability of a technologically advanced life.

Stephan Turnipseed

Executive Vice President and Chief Strategy Officer

“We’re preparing them to have skills,” K-12 Director of Innovation and Technology Cary Johnson says of PYLUSD learners. “We don’t know what their jobs are going to be like, five, 10, 20 years from now. They need to have the skills to be adaptable for the future. STEM, by its nature, is problem-solving, thinking through issues, and being cross-disciplined.”

Students recognize the seismic paradigm shift underway in education and are eager to amass the tools needed to create a better world. Zoe, a PYLUSD eighth grader, says the engineering design process inherent in lab activities “helps to improve your project after it’s done no matter what you’re doing…You have to rethink it and then go back and improve it.” Her classmate George imagines how his open-ended lab experience will eventually pay dividends. “I think it’s pretty useful because everybody will face failure, and they need to improve due to failure.”

Such open-mindedness is a natural byproduct of a learner-centric, engaging educational experience aimed at preparing young people for life, whatever form it might take.

The role of education successfully evolved from the 18th- and 19th-century mandate of teaching English and basic skills to the 20th-century call to address mass manufacturing and the evolving family. Now, it must evolve to prepare children for the greatest, most challenging adventures of their lives—operating professionally and personally within a society dominated by more and more technological innovation, not least of which will likely be self-aware machines.

Because these new norms do not yet exist, we cannot directly prepare younger generations for them. This is why, in order to yield positive outcomes for young people and their collective future, we need to prepare them for the unpredictability of a technologically advanced life—not just the fourth industrial revolution.

New resources and news on The Big Idea!

×

We recently announced a new R&D acceleration initiative to connect and support local communities ready to bring public, equitable, learner-centered ecosystems to life.