Wearing All the Hats During COVID-19: A Conversation with Nayan Bhula

Q&A 31 March 2020

By Nayan Bhula, Education Reimagined

Trying to approach things in a more learner-centered way, I asked everyone what activities they would take on if they could choose absolutely anything. With the older group of kids, I got crickets. They couldn’t articulate what they were interested in.

Nayan Bhula

Operations Manager, Education Reimagined

Nayan Bhula is the Operations Manager for Education Reimagined. And, he is a parent of two children—one 9-year-old and one 11-year-old. This conversation explores what it was like for Nayan, his family, and his neighborhood to manage the literal overnight transition to working and “schooling” from home. This conversation took place on March 23rd and notes have been added to reflect what has changed since that time.

As one final note before diving in, Education Reimagined recommends all families follow the guidelines provided by their local health officials and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention to help curb the spread of the coronavirus.

Q: The week of March 9th marked a big wake-up call for the United States that this pandemic wasn’t going to be a short-term concern. What was that week like for you and your family?

Nayan: On Thursday, March 12th, our school district sent an email to families letting us know schools would remain open the next day, but would be closed the following week. One of the original intentions for having the schools open for one more day was to give everyone the opportunity to pick up their books, laptops, and other belongings. As soon as I read the email though, I thought, “This is not going to go well.”

The tone of the email was off. They mentioned “the coronavirus risk in our community remains low.” Any risk at all wasn’t comforting. It sounded like they weren’t taking the situation seriously enough. Although things were being cancelled left and right around the country, they were doubling down on what our local health inspector was saying—basically, that everything was fine.

This tone of “everything is fine, just go about things like normal” didn’t match what we were seeing in the news. That evening, parents began brewing—asking questions and expressing their concerns about their children attending school the next day. By 11:40pm, a second email was sent out saying the county had heard everyone’s complaints and that school would be closed the following day. This wasn’t surprising to me given the tone of the first email and the parents’ collective reaction as the evening went on.

Editor’s Note: As of March 31st, families have still been unable to retrieve the belongings left at school on March 12th.

Q: What has your district done since closing things down on March 13th? What has learning looked like in your home?

Nayan: The county we live in is very large, which is part of the issue. They don’t have the luxury of giving everybody a laptop or an iPad like some counties do. They can’t implement ideas that don’t work for all children. They have provided grab-and-go lunches at certain schools and at certain times of the day.

Emails from teachers have been pretty vague—providing some minor homework and chapters for reading here and there. But in general, we’ve been left to our own devices. This lack of guidance jump started a conversation between a few families and ours about how we would balance managing our kids and getting our own work done with our day jobs.

Things began moving really quickly. One of the dads—who we’ve dubbed “the principal”—emailed everyone on Saturday morning (March 14th) saying (real names have been replaced):

Folks,

I started a schedule to homeschool over the next 4 weeks? I just filled in Monday [in a spreadsheet] to get a sense of what it could look like.

Goals:

provide structure

keep things “normal”

get the kids out so we don’t strangle them 🙂

I’m making some assumptions:

split up younger kids and older kids

Jerry and Roger may be unavailable at some point

the school will provide some guidance, but we may have to make it up for a while

An extra parent or two would allow for “subs”

I didn’t include Jeremy or Sarah yet. They may want to join. Larry’s nanny is French, kids will love to have to continue with French class 🙂

Let me know what you think.

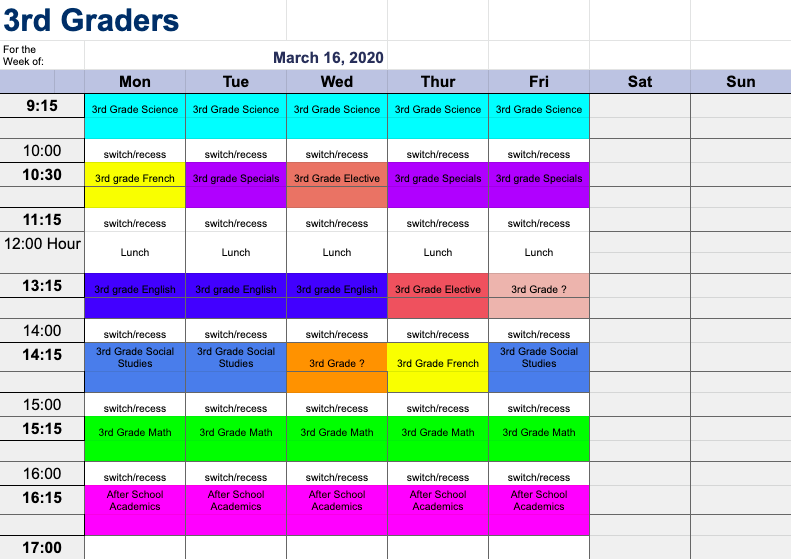

After everyone provided some input based on their availability, we ended up with the following schedule where each color represents a different parent-teacher and household. Basically, the kids biked to different houses within a half mile radius and would spend a couple of hours at each place—giving everyone who didn’t have to provide learning during certain time blocks the space to focus on their day jobs:

Some families who were invited to participate said “no thanks” because they were hunkering down. And, that was something that made us question if this was the right thing to do. Our kids would literally be going from house to house on their bikes and back home when the day was done. So, it didn’t seem like the smartest thing to do if you looked at the calls for social distancing. We were following those guidelines outside this effort, but we saw this through a different lens.

Overall, we began with five families participating in this effort and called our “school” The Zombie School of McLean. We didn’t want to add more so we could keep it under 10 people in each house. The subjects each of us teach are based on our interests and skills. Parents have experience in mathematics, science, music, and art. Some families have high schoolers who are also helping teach. We are all just leaning into our interests and what we already have background knowledge in.

Q: How did the first week of this learning experiment go?

Nayan: The first week went really well. The kids are learning and having a good time. I think the big thing for us parents has been noticing how important it is for kids to be with other kids. The camaraderie that comes with that, especially when everything else is shut down, is really valuable. The kids are definitely more motivated by being together first and the learning second.

But, the learning has been exciting for them. I did stop animation on the first or second day and by the end of the week, one of the kids was so into it that he downloaded the application at home and was already making his own movies. It was really cool.

A comical stop-motion film made by a group of young learners (in less than one hour) who participated in the homeschooling effort—The Zombie School of McLean.

Of course, things come up for all of us parents, so we have to communicate if our time to teach is no longer available. And, this is kind of funny how structured this is, our “principal” has someone helping us out as the “scheduler.” We can email the scheduler and say, “Hey, I have a meeting at this time now. Can you find a substitute?” They will jump in and call other parents and find someone who can help out.

It’s been really incredible to see how quickly all of this was put together and how every family is leaning into this. The fact that we have teenagers, nannies/au pairs, and someone who can act as the scheduler makes it really effective. Parents are downloading PBL packets; I’m researching new ideas for music, art, and PE activities. It’s motivating to continue creating when you know other parents are doing the same for your own kids.

At the end of the day though, this is all being reassessed on a weekly basis. Depending on how things move with the pandemic, we’ll adjust accordingly.

Editor’s Note: As of Friday, March 27th, two families chose to keep their kids at home given the rising COVID-19 case count. And, as of March 31st, the state issued a strict stay-home order that has put a permanent end to this unique homeschooling effort. The families will be exploring how they might continue staying connected via video.

Q: What’s an interesting thing you’ve learned while implementing this at-home learning experiment?

Nayan: The older group (all boys) have been a ton more difficult than the younger group. And, not necessarily for the reasons you may think. The older group is so used to having a strict routine that getting them to do anything in a non-classroom setting is really difficult. Trying to approach things in a more learner-centered way, I asked everyone what activities they would take on if they could choose absolutely anything.

With the older group, I got crickets. They couldn’t articulate what they were interested in. I tried to get them thinking by pointing out obvious points of interest in the room we were in. “Are you interested in knowing how that table was built? Are you interested in understanding how Bluetooth works?” The idea behind asking this question was to help them start a research project. But, more crickets.

Rather than give up on that conversation, I’ve decided to further it by asking them why they believe they struggled so much coming up with an answer. Was it because they were embarrassed to say they were interested in learning about broccoli, you know, something silly like that, in front of their friends? Whatever the case may be, it was really interesting to see them struggle so much answering what they are interested in.

Relatedly, it’s actually interesting to see how each parent approaches their teaching. Our “principal,” who also took on teaching math, was in conversation with the kids’ math teachers in the beginning to tackle things more conventionally. But, after a little while he began searching for richer learning experiences. The rest of us jumped into things wanting to do it our own way.

Personally, I wanted to try some new stuff. I want to expand beyond a specific subject and see what bigger projects the kids might want to involve themselves in. I want them to lead it and see if I can’t break that “tell me what to do, teacher” mentality.

I can easily get the younger kids excited about learning all sorts of things, but it seems that general interest in learning is no longer there for the older kids. I want to provide the space to help change that, if I can. I want to bring that joy back.

Q: What’s it like having to be the person who is constantly creating new ideas all the time?

Nayan: It’s draining. I was pretty tired during the first week, so I emailed the group and requested a couple of days off the second week. We’re working on so many things at Education Reimagined that I needed to make sure I could remain on top of those things. I needed to catch up. Constantly switching hats all day from parent to teacher to chef (lunch) to employee is difficult, even with the support from other families.

It makes sense why a parent would opt for more conventional ways of educating their kids during this time. Thinking about trying something new or different is difficult enough when there isn’t a pandemic going on. It demands a lot of creativity and research. And, as I’ve attempted to do things differently, I know I’m only adding to my fatigue. But, it has been more fun for me.

Q: What are some of the activities you’ve had the kids participate in?

Nayan: The first idea I came across was for a stop-motion project. Additionally, a friend of mine who is an actress has been producing “Corona Tapes” where she takes scenes from famous movies and acts out the scene and plays every character herself. I thought that was a cool idea, so I did it with the kids using iPhones and trying to exactly match the scenes and lines from movies. Each group tried to recreate a scene from Sandlot as for many our baseball/softball seasons were canceled (view their work here and here).

I spent ten years running a music school and have a workshop that shows kids how to write a song in 45 minutes, so I was able to pull that out of my back pocket. I set up a keyboard, guitar, some percussion instruments, and a microphone. We even had kids learn to record themselves on GarageBand. Though the song was created in one hour, the tracking took us a few hours over two days. Although most of the kids had zero previous musical experience, they created something special. It was awesome to see.

Q: How has working at Education Reimagined impacted your approach to teaching?

Nayan: Being around our communities and talking about learner-centered education with friends and family has made me believe this type of learning is doable. When I knew school was shutting down, I honestly thought it might be a blessing in disguise. I’ve never had the avenue to pursue this type of learning with my kids. There’s no school in our area that offers learner-centered learning. Being a part of this work allowed me to look at a lesson plan online and think about it so much differently than I would have in the past. Rather than thinking, “Ok, here’s what I’ll tell them what to do,” I was thinking, “I want them to tell me what they want to do.”

I think if we can just turn on that switch—thinking about how we can have our kids see learning as joyful—it’s a game changer. When we ask our children what they’re interested in and they can’t answer—literally can’t come up with any kind of answer—this moment of at-home learning is an opportunity to rethink the education of our children.

New resources and news on The Big Idea!

×

We recently announced a new R&D acceleration initiative to connect and support local communities ready to bring public, equitable, learner-centered ecosystems to life.