3 Critical Components for a Reimagined Education System

Voices from the Field 09 April 2019

By Stephan Turnipseed, Pitsco Education

When we fully embrace and assume the accountability for a learner-centered education, the impossible becomes possible.

Stephan Turnipseed

Executive Vice President and Chief Strategy Officer

The world of work in 2030—what will it look like? At this point, we can only speculate because even the most learned among us offer competing predictions.

For some, the specter of technological unemployment leaves millions of workers stranded; for others, a technological society opens limitless possibilities for new and remarkable jobs for humans. And, for the rest, a sort of middle ground exists, where society embraces an egalitarian notion of work and creativity leads to an enlightened age of work—a sort of modern-day renaissance.

No matter which view becomes reality, we know those entering the workforce in 2030 are in the first grade today. Preparing them for this unknowable future requires reimagining our education system and, perhaps more importantly, reimagining the roles within the system.

For most of the industrial age, education largely kept pace with the economic and societal needs of the western world. As the earliest adherent to this phenomenon, the US led the world in establishing universal elementary education with the Mann reforms and the common school.

The continuing shift from an agrarian economy to an industrial one led to yet another innovation, termed the “high school movement.” This movement was intended to supply workers and citizens for the growing world of mass manufacturing. In each of these cases, the economy demanded sharper workers to fuel the engines of progress and economic growth.

Exponential change demands a shift in dialogue

We once again find ourselves in a world where the changing demands of the economy require a better-equipped, technologically-astute worker and citizen. However, this time around, the rate of change is exponential, not arithmetic or geometric. This is creating an unprecedented demand for workers who are prepared for an undefined future.

As a result, business and industry are rethinking job demands to decide whether a college education is actually required and if not, then what the requirement is. Is it a solid high school background in the classics and trades, as was the case during the high school movement? Is it a stronger vocational set of skills as seen in some European educational systems? Or is it all this and much more?

The Partnership for 21st Century Learning first brought forward the notion of “much more” with the 4Cs (creativity, critical thinking/problem solving, collaboration, and communication) in their groundbreaking work 13 years ago. This work was fully accepted and supported in 2016 by the National Academies Report: “Education for Life and Work: Developing Transferable Knowledge and Skills in the 21st Century” (James W. Pellegrino and Margaret L. Hilton).

This report was further amplified by august works in subsequent years that evolved these 4Cs to be defined variously as soft skills or employability skills in the general parlance of the current economic debates surrounding education. Yet, almost no one in the field has demonstrated clear guidance as to how to achieve the promise of the high school movement with the 4Cs or the notion of grit (perseverance and character) added on.

Even the community working broadly in the field of reimagining education has struggled to achieve a workable, scalable model of education that prepares children for this new world. In large part, this is due to the residue from the No Child Left Behind test-and-punish paradigm of evaluation.

In this system, the outputs are graduates. If the output is deemed unacceptable, firing the operators (a.k.a. teachers) and declaring oversight of the machines (a.k.a. schools) is the solution. This unfortunate result has fueled the debate around choice as governance, rather than learner preference based on the learner’s stated needs.

It is time to shift the dialogue to one of inputs and relationships rather than outputs and rules. In an input-driven model, the system is dynamically altered based on the process of personalizing student learning and periodic inspection of the product along the path; this is called statistical process control in industry and called formative assessment in education. In this model, there are three critical components: talent identification, workforce readiness, and community impact.

Talent Identification

Talent identification begins with the relationships among the various stakeholders in the life of a child. To ignite children’s passions, at the earliest ages, they must be exposed to a variety of career opportunities and mentors in the workforce—including individuals who have backgrounds similar to their own. In an open-walled, socially embedded education, the community actors (business, policy, parents, and so on) partner with the schools to help define what the future jobs will look like and provide role models and field experiences in the world of work and civil society.

Children will self-identify when their passions are ignited, and they can see themselves in the example of the role models they encounter. My favorite example of this important phenomena is my friend Leland Melvin, a former NASA astronaut. During his time as NASA Associate Administrator for Education, he was visiting a school serving a low-socioeconomic community, where he encountered a young African American boy who would not believe that Leland—himself an African American—was an astronaut. The young man was convinced there were no black astronauts.

After a significant amount of fact building by Leland, the child finally came to realize that he, too, a space enthusiast, could indeed become an astronaut. This fact is underscored in Leland’s book Chasing Space, where he points to the importance of role models both in his personal life and in his work in the NASA Summer of Innovation campaign in 2010¹. “I saw it as a chance to use my blue astronaut suit to inspire the next generation of explorers, especially those who didn’t always have opportunities in the STEM fields.”

For too long, members of the business community have remained on the sidelines, marginalizing their legitimate power to inspire children through their personal stories and experiences—preferring to engage in checkbook philanthropy, rather than run the risk of being real with children. I freely admit, after having been interviewed by a fourth-grade class at AB Combs Leadership Magnet Elementary School in Raleigh, NC—an experience significantly more intimidating than any corporate board I have ever faced—there is risk. However, the rewards are so much greater when one considers the grander risk of losing the potential in each child because of the timidity of adults in their lives. Again, it is about the relationships and not the rules.

Workforce Readiness

The second component is workforce readiness. This is a process of beginning with the end in mind, as author Stephen Covey wrote in his acclaimed book, The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People. In education, beginning with the end in mind often involves creating the profile or portrait of a graduate.

“Don’t we already have such education plans?” you might ask. Yes; however, they are defined by standardized test scores, rather than practical involvement within the community to determine the best way forward.

“Don’t we already have such education plans?” you might ask. Yes; however, they are defined by standardized test scores, rather than practical involvement within the community to determine the best way forward.

Battelle for Kids, a national not-for-profit organization, has pioneered this portrait work with school systems across the US. As one of many examples, the Henrico Learner Profile showcases the roles of each actor in a child’s life, both in and outside of the school building. In their model, the question is: “What does it mean to be life ready?” The answer is not about academics, although those are important. Instead, it is focused on the soft skills and social networks found in the community as the keys to children’s future success.

Community Impact

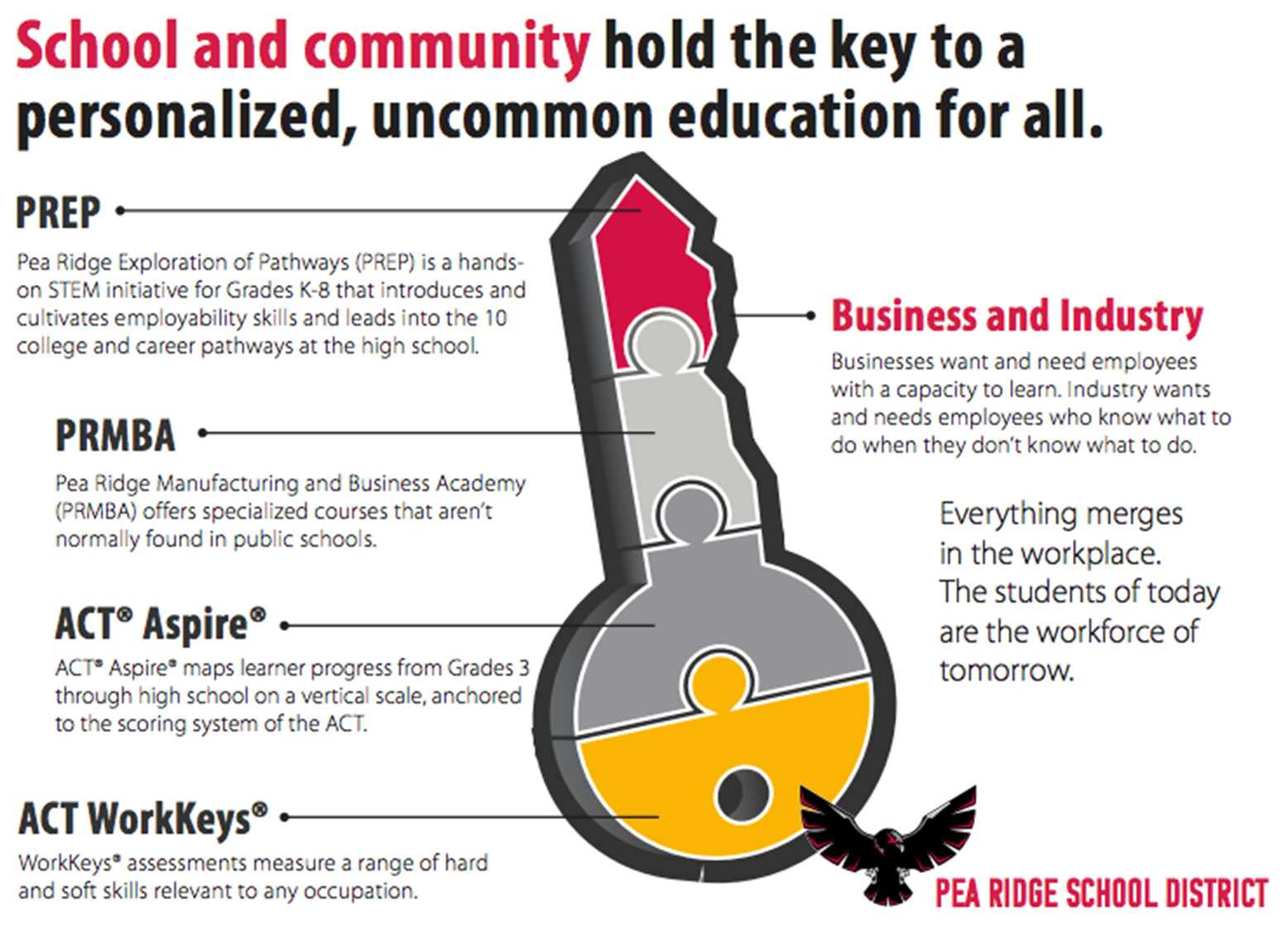

The larger question, however, is how to foster these life skills in children to ensure community impact. At Pea Ridge Public Schools, AR, this approach, again in concert with the community (including business and industry), builds on what they call “the key to a personalized, uncommon education for all.” As shown in the graphic from Pea Ridge, the role of education as a provider of only academics is turned on its side. All children are shown a sure path to the world of work by providing relevant industry-level experiences. This is accomplished through elementary and middle (PREP) and high school (PRMBA) programs delivered in the context of comprehensive academic schools.

“Schools are notoriously territorial of their educational principles and values, and business and industry have never been a part of the conversation,” Pea Ridge Superintendent Rick Neal said. “When we opened that door, business and industry came right through. Everybody that I have a conversation with in business and industry, they understand it. They get it. They want to be a partner in educating their next employees, rather than waiting on the next employees to be trained by them.”

Finally, success is measured in the community impact these children have as they progress through and depart from school into the larger world of work and civil society.

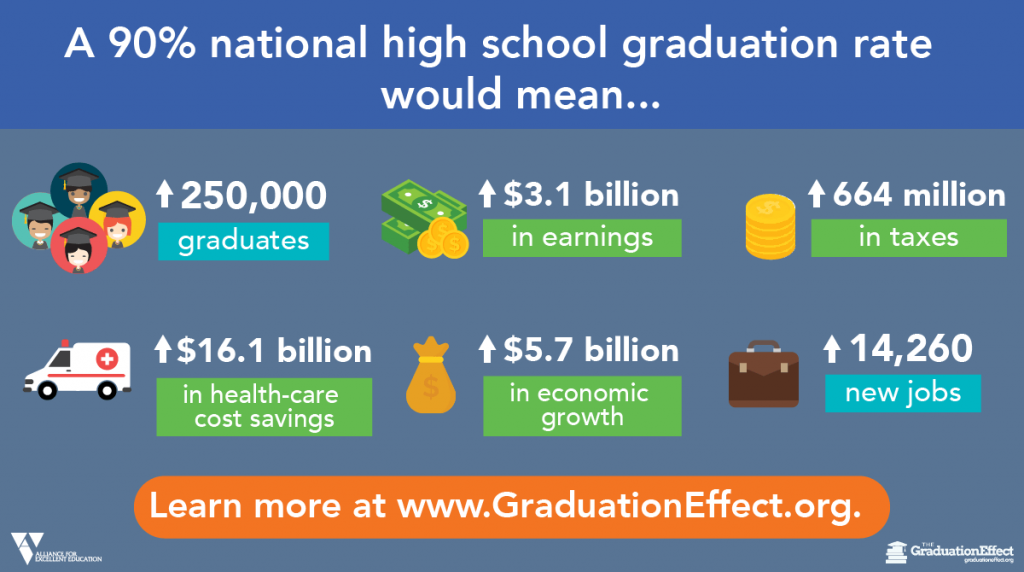

Bob Wise at the Alliance for Excellent Education makes the following national argument:

“For the Class of 2015, which had a graduation rate of 83.2 percent, a 90 percent graduation rate would have meant an additional 250,000 students would have walked across the Commencement Day stage. These graduates would collectively have earned $3.1 billion annually in additional income.”

This point is further illustrated in the following graphic included with Wise’s article.

He goes on to state: “Please keep in mind that while All4Ed’s economic model is based on a 90 percent high school graduation rate, simply pushing students through the system to make sure they earn a diploma is not the answer. The high school diploma that students earn must represent the content knowledge, critical thinking, collaboration, communication, and other deeper learning skills necessary for success in college and today’s economy.”

Or as I have previously written, children who possess the mind-set, tool set, and skill set required for life beyond the fourth industrial revolution will be prepared to fill the workforce pipeline in 2030. Their success will be measured in community impact.

Will we take advantage of this opportunity to transform?

Rarely are we presented with such an opportunity, in the face of such significant need, to materially affect the course of children’s lives as we are today. With near-universal access to technology and the warp speed of innovation, our children stand on the steps of a brave new world.

At the same time, children in the US express the lowest levels of trust ever recorded in their schools’ ability to secure their future. More importantly, this lack of trust from our children is mirrored by our lack of trust in them as architects of their own passion and learning. This lack of trust in our children is evidenced by the very adult-centered debates over Common Core, teacher quality, and school choice as governance, rather than the ones that really matter to our children, such as equity, access, and safety.

Most of us reading these words have grown up in an economy and education system that worked well enough for us. These powerful images of our past can cloud our judgment of the present. These facts of our past cannot be counted on to effectively inform our present, given the different circumstances we are now facing. However, they often do, and we as a people seem ill-equipped to deal with the challenge before us.

When we fully embrace and assume the accountability for a learner-centered education, the impossible becomes possible. The call to action now is for all stakeholders to engage in dialogue through the process of talent identification, workforce readiness, and community impact.

The path to regaining the trust of our children is through giving them control of their personal trajectories, first through trusting relationships and then, only when necessary, through rules. In the cities and towns of our country where we see this happening is prosperity that can be a beacon for others to follow.

Perhaps this notion is best summarized by Booker T. Washington. “Few things help an individual more than to place responsibility on him, and to let him know that you trust him.”

¹ This innovative educational campaign was designed to help underserved and underrepresented students overcome the “summer slide,” during which they were likely to lose ground academically. Research has shown that this slide forces them to play catch-up the next school year, often leading to an ever-increasing gap between them and on-grade level students.

New resources and news on The Big Idea!

×

We recently announced a new R&D acceleration initiative to connect and support local communities ready to bring public, equitable, learner-centered ecosystems to life.