The Time Has Come for Assessment that Matters

Voices from the Field 09 April 2019

By Dr. Elliot Washor, Big Picture Learning and the Met Center

Education is one of the few fields, and perhaps the only system, that neither changes its standards nor the way it measures those standards as society transforms.

Elliot Washor

Co-Director

It was 1995 when Ernest Boyer, then president of the Carnegie Foundation, stated, “The time has come to bury the old Carnegie unit; since the Foundation I now head created this unit of academic measure nearly a century ago, I feel authorized to declare it obsolete. Why? Because it has helped turn schooling into an exercise in trivial pursuit.”

Nearly 25 years later, Boyer’s critique of our standardized standards still rings true. “Students get academic ‘credit,’ but they fail to gain a coherent view of what they study. While curious young children still ask why things are, many older children only ask, ‘Will this be on the test?’” What does this tell us about what the system values?

Education is one of the few fields, and perhaps the only system, that neither changes its standards nor the way it measures those standards as society transforms. The same old system of standards just gets more standardized.

Outside of education, we often see industry standards change on an annual basis. An example is the health industry. In February 2018, New York Times journalist, Anahad O’Connor wrote a piece: The Key to Weight Loss Is Diet Quality, Not Quantity, a New Study Finds. Over the course of a year, two cohorts of people—totaling 609 participants—were either placed on a low-carb or a low-fat diet. The goal was to see which diet had a stronger impact on weight loss (spoiler: Both diets worked).

Despite the fact that only 19% of US workers report using basic algebra, we continue to use Algebra 2 as a gatekeeper for college admissions.

Dr. Elliot Washor

Co-Director

Yet, even though both diets worked, the study, published in JAMA, had an interesting finding: “People who cut back on added sugar, refined grains and processed foods lost weight without worrying about counting calories or portion size.” With a single study, we can already begin shifting our belief (rather willingly) that weight loss is no longer about counting calories. Using the weight loss discovery as a parallel, wouldn’t it be great if we counted less and started measuring more for quality in our students’ work.

When new, scientifically-backed information arrives in the health industry, why are they so willing to change their standards? Of course, the better question is why does the education system remain so unwilling to change when study after study proves many of our practices are no longer relevant? For example, despite the fact that only 19% of US workers report using basic algebra, we continue to use Algebra 2 as a gatekeeper for college admissions.

Not only in health but also in so many other professions and trades, there is increasingly more attention being paid to ensuring quality and equity—which is having a direct impact on how they think about their own standards. Recently, The James Beard Award (which recognizes culinary professionals in the US) got ahead of the curve when they assessed contestants for: “The values of respect, transparency, diversity, sustainability and equality,” as well as taste and service. After they did this, guess what? The number of women and the overall diversity of people winning the award has dramatically increased, and the variety of foods and how they are served have changed significantly. They achieved equity through changing the standards, not standardizing.

In education, we act as historians and accountants—collecting and analyzing endless streams of data focused on a narrow vision that leaves little room for change—rather than being inventors and trend setters. If we identified as the latter, how could we compare today’s 12-year-old with one from 1919? Then again, after collecting over 100 years of homogenous data, what do we have to show for it? We can’t expect to close equity gaps and provide higher quality education while relying on the system that created such gaps in the first place.

As Mark Twain said, “Supposing is good but finding out is better.” We need to collect different and better data using different and better measures that look more broadly and deeply at each and every student. This data collection needs to be connected to teachers being allowed to use their judgement, skills, and experience. It can no longer be detached, impersonal, and imposed solely by distant assessors (i.e. state exams).

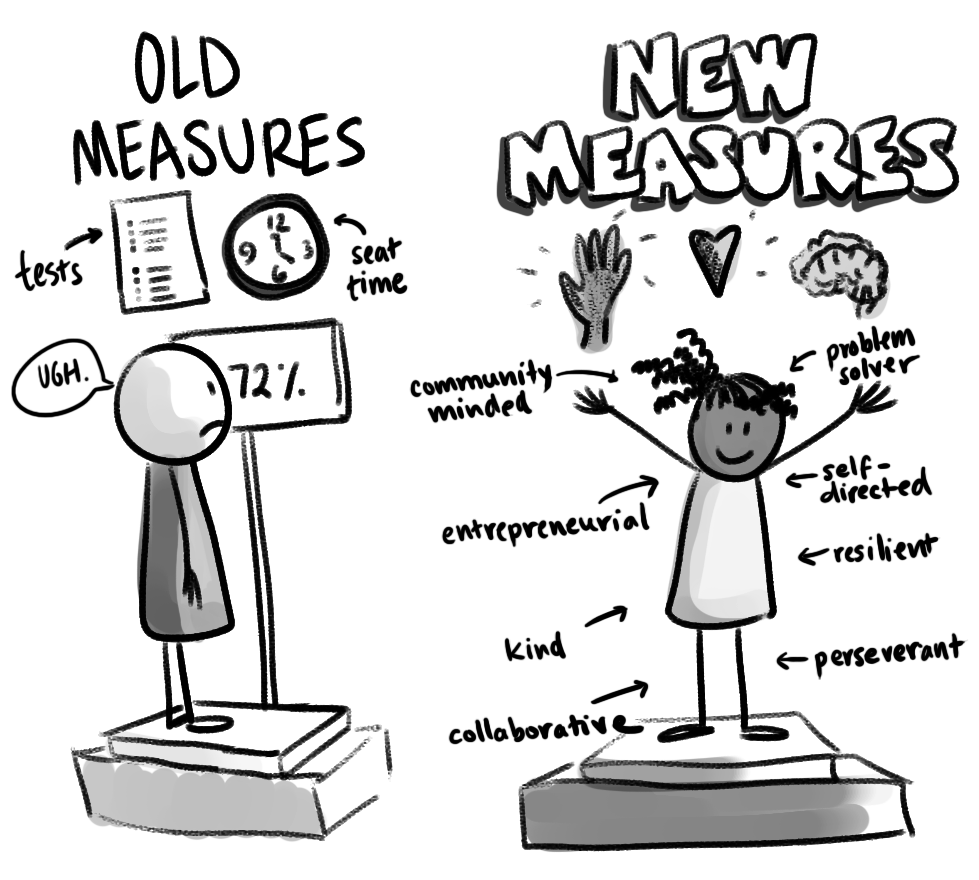

In fact, one can only ask that we look at new measures to get us out of the mess we are in. Given that in so many other fields and professions there are new and different measures, we have to ask the question: Does our old data set and the way we collect it prevent us from seeing the bigger picture? Or, is it something more intentional that maintains underlying biases and a status quo for only certain people?

Our current system is set up to have a laser-like focus on standards that might not even be telling us what we most want to know about how our students are doing.

Dr. Elliot Washor

Co-Director

When talking about new measures, empowering and trusting educators to assess those measures, and what is keeping the status quo in place, we have to look at how equity is being handled. This brings to mind recent work I’ve seen by Danique Dolly, a Harvard Ed.L.d candidate doing his residency at New Harmony High in New Orleans, a school in the Big Picture Network.

He came up with an Equity Map that was based on the work of Robert Kegan and Lisa Laskow Lahey’s book, Immunity To Change. The Equity Map is a tool for operationalizing equity in schools, or said another way, a tool to help “diagnose and strategize different ways to make equity real in your school.” The Equity Map allows school leaders and teachers to spend time identifying an equity target and unpacking it.

One aspect of the tool asks leaders to look at whether there are “hidden competing commitments” that are getting in the way. Danique points to this as something often overlooked and the reason many well-intentioned equity plans never get operationalized. Having schools take on the work of addressing issues of equity and diversity is an important first step not only in enabling their school leaders and teachers to be the agents of collection, judgement, and change in their schools but also because it has them start to look beyond those reworked standardized standards we still keep tracking.

At the end of the day, our current system is set up to have a laser-like focus on standards that might not even be telling us what we most want to know about how our students are doing. This is like Andrew Carnegie’s advice to Mark Twain: “Put all your eggs in one basket and watch the basket.”

Rather, we might look at Ernest Boyer’s closing words, “I hope deeply that in the century ahead students will be judged not by their performance on a single test but by the quality of their lives.” Boyer was asking the important question: “What, then, does it mean to be an educated person? It means developing one’s own aptitudes and interests and discovering the diversity that makes us each unique. And, it means becoming permanently empowered with language proficiency, general knowledge, social confidence, and moral awareness in order to be economically and civically successful.” What standardized test measures this in our students? Shouldn’t this be the standard of our school system?

New resources and news on The Big Idea!

×

We recently announced a new R&D acceleration initiative to connect and support local communities ready to bring public, equitable, learner-centered ecosystems to life.