Education Equity: Setting the Context for a Robust Conversation

Insights 22 January 2019

By Ulcca Joshi Hansen, Education Reimagined

If you choose to stick around for this conversation, and the many that will be had in Voyager throughout 2019, I promise you will find yourself exploring, discovering, and expanding within a community of learner-centered leaders who don’t have a second to waste either.

Ulcca Joshi Hansen

Associate Director, Education Reimagined

Although I wish it were so, the issue of educational equity can not be adequately addressed in a 2,000-word piece. Although I wish I could, I can’t guarantee that in 10 minutes we will all be up to speed on the challenges and most viable solutions available to us. I wish I could accomplish such a feat because the longer I request your attention, the less likely you are to stick around. Not because you don’t care, but because you are trying to grapple with the tension of wringing out the best possible outcomes for the young people you serve. All while living inside of educational, social, and economic systems designed to create disparate, and often unfair, outcomes.

As much as you would love to stick around, you have work to do. Work that doesn’t care if you’ve finished reading this or any other article on educational equity. Work that is an unrelenting, 24/7 challenge with infinite pathways of possibility and impossibility. Work that invites you to give up every day, but because it transforms the lives of children, persuades you to come back without a shadow of a doubt. The kids you serve, be it locally, regionally or nationally, are worth fighting for, regardless of the day-to-day shifts you see (or don’t see) in the decades-old struggle for educational equity.

With that said, here is my promise to you: if you choose to stick around for this conversation, and the many that will be had in Voyager throughout 2019, I promise you will find yourself exploring, discovering, and expanding within a community of learner-centered leaders who don’t have a second to waste either. And, who also commit to making a contribution to the national movement by engaging in this conversation.

Since joining Education Reimagined, I have been so inspired by the honest, sometimes raw, sometimes difficult conversations I have had a chance to have with many of those in our network about what it will take to ensure that every single child in this country has an opportunity to live into their full potential.

Launching as a brand new organization in 2019, we are excited to be curating a series of articles in which we will be exploring the idea of educational equity as it relates to the learner-centered paradigm and the transformation of our education system. These articles don’t pretend to have the answers, but they will be an invitation into conversations about these complex issues as they relate to the future we are trying to create together.

My reflections and ideas have been shaped by visits to dozens of learner-centered environments around the US and internationally, and conversations with hundreds of learner-centered practitioners, both inside and outside of learner-centered environments. I am so grateful to the learners, educators, and families who have been willing to share their successes, challenges, and evolving thinking about what it means to create authentic learner-centered experiences for young people.

As the first author in this series, I want to provide a road map for the questions we will be tackling in this and future pieces:

- How should we think about what educational equity entails?

- If we shift to a focus on individual learners, how do we ensure we are setting appropriately high expectations for each and every young person, especially in light of embedded biases and beliefs about who is and is not “capable”?

- Does learner-centered education run the risk of being so hyper-individualistic that it risks not providing young people with everything they need to succeed in life?

- Why does equity demand equal if not stronger focus on educational transformation than on incremental innovation and reform of the current system?

- How are the challenges that emerge inside of a learner-centered system different from the challenges that reformers of the school-centered system are focused on solving?

Omayra engaged with my children on a level that eluded and challenged me. She knew my learners’ world: the richness of their community; the aspirations of their families; the internalized hopelessness they carried into my classroom.

Ulcca Joshi Hansen

Associate Director, Education Reimagined

The first time I saw Omayra, I knew she mattered. In a neighborhood where crushed crack vials and occasional shootings were as much a part of the culture as lively Hispanic rhythms, Omayra had experienced it all.

She wasn’t much older than me, but her gaze possessed a cool confidence that mine lacked. “You be wasting your time here,”she remarked matter-of-factly as I walked towards the school one morning. It was the start of an extended conversation.

I’d recently moved to Newark, NJ where I started my first year of teaching in the stifling basement classroom of a public elementary school. I’d caught glimpses of the critical state of children’s lives in Newark while working with a local non-profit, and knocking doors as a campaign volunteer, and I promised myself that my teaching would make a difference in the lives of my 38 children.

That fall, I found myself watching Omayra through the glass doors of the school. She was a drug dealer, yes. She and other dealers helped create conditions that ravaged the neighborhood and my kids’ families. And yet, she was also a teacher.

She engaged with my children on a level that eluded and challenged me. She knew my learners’ world: the richness of their community; the aspirations of their families; the internalized hopelessness they carried into my classroom. She helped them cope with struggles I barely understood, and she earned their trust and respect in the process.

She was also my teacher and a guardian of sorts. I lived in the neighborhood. I did home visits, let kids stay after school, and stayed late planning. And, Omayra knew it. A couple of months into the school year, I noticed my car windows were never broken, my car was never keyed, and I felt strangely safe exiting the school doors well past dark.

There was a remarkable irony in our individual stories. Omayra and I were actually born in the same Newark hospital, both to immigrant parents whose economic circumstances led their young daughters to experience uncertainty and displacement during our formative years. Our stories might well have converged in a totally different way but for the small ripples of life that carried us in divergent directions.

My displacement ended in security. Omayra’s didn’t. I did well—in large part because my parents made difficult choices that enabled them to buy a home in the suburbs, where I had educators who took an interest in my success and had the flexibility and resources to act on their interest. It wasn’t until I got older that I realized what it said about the US education system—how equity of opportunity could require so much sacrifice on the part of families, and still leave so many children like Omayra behind.

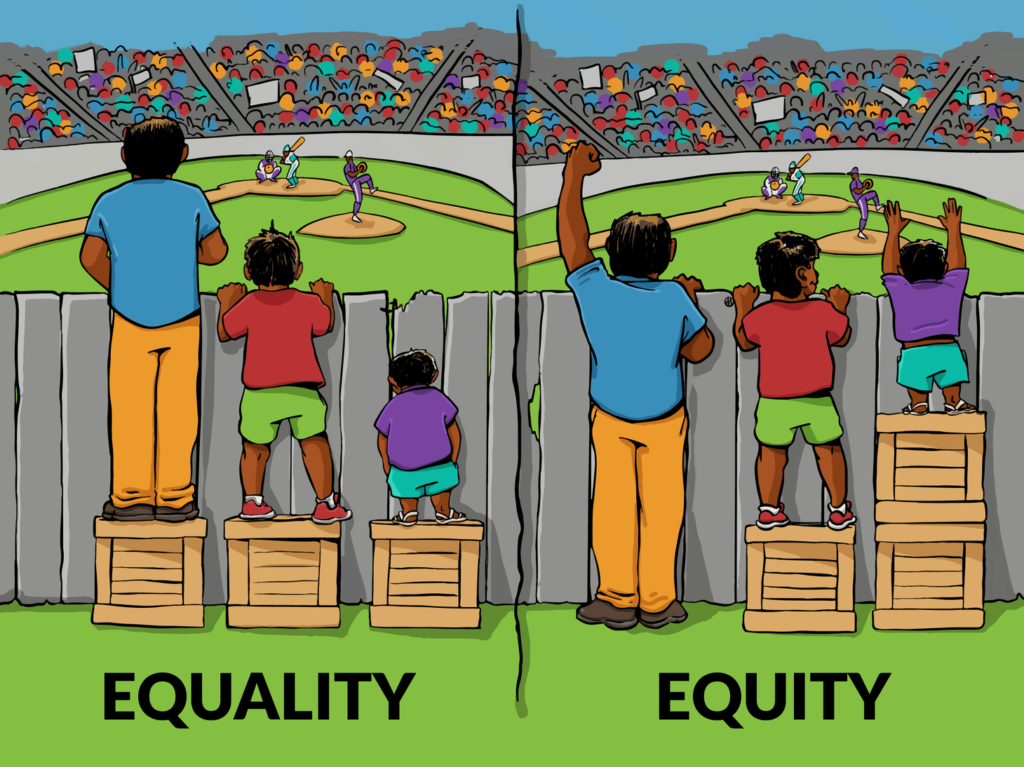

Some of you may have the educational cartoon above. When I began teaching, policymakers were enthralled by that cartoon’s second frame—the idea that “equity” means helping all kids see over the fence—which they conflated with scores on standardized tests of basic subjects.

As a teacher, I watched in frustration as kids, fascinated by the bubbly chemistry between baking soda and vinegar, wilted in the face of paced literacy and math curricula; and became “academically underachieving” during tedious weeks of testing. Innovation grants from funders meant learners got PlayStations for literacy games to improve test performance, but their basic nutritional, mental and emotional needs were neglected. Many of them would quit—as Omayra did—alone and frustrated.

I believe with all my heart that the only way we will succeed in helping all young people develop into thriving adults is by transforming our education system from a school-centered one to a learner-centered one.

Ulcca Joshi Hansen

Associate Director, Education Reimagined

Parker J. Palmer writes in The Courage to Teach that “to educate is to guide learners on an inner journey towards more truthful ways of seeing and being in the world.” I learned from Omayra that until I opened myself up to my learners’ world, I would never reach them at the deeply human level they needed most. My lessons would remain intellectual exercises, instead of serving as opportunities for personal growth.

I believe with all my heart that the only way we will succeed in helping all young people develop into thriving adults is by transforming our education system from a school-centered one that emphasizes standardized notions of success; to a learner-centered one that recognizes that each child has unique gifts, and each will take a non-standard path to maximize the potential of those gifts.

This shift requires freeing ourselves from outdated notions of “success” and “equity” that too often reflect privileged, culturally-biased perspectives. I think of this shift in two parts: equity of the “learning experience” and equity of the “human experience.” In some ways, this is an artificial distinction. But, I find it useful to think about these two aspects separately.

Our current education system has built in and maintains inequities across both domains that must be addressed if every child is to have access to educational experiences that empower them to achieve their unique potential and prepare them to live fulfilled and meaningful lives. Using this distinction and the journey I’ve embarked on over the last 20 years in this field, let’s explore a powerful way to start thinking about equity from a place of possibility.

Equity of the Learning Experience

Let’s start with the “learning experience.” The conventional, school-centered model was designed to get every kid to “average” or “normal” or “standard” according to the “minimum bar” definition set by the system. Ever since then, and increasingly so since the US accepted the moral obligation and economic necessity of educating all young people, we’ve been trying to jerry-rig this system.

But again, it was designed to sift and sort kids—not serve all of them. In recent decades, we’ve tried to raise the minimum bar through more rigorous, expansive, and common sets of knowledge and skills, and we’ve tried to improve the efficiency of the system by focusing on more effective teaching, earlier intervention, and more testing. But, in doing this, we have only created new and different ways of under-serving children.

We label and stigmatize kids whose cognitive strengths are different from some abstract idea of “normal” that underlies our standardized frameworks. They have dyslexia or “learning differences.” They are autistic or have “special needs.” Or, they suffer from vague emotional or affective disorders—many that reflect frustration with a system that can’t meet their needs.

To safeguard against low expectations we rely on standardized, “objective” measures. But, these tests have inherent cognitive and cultural biases, which prevent many learners from demonstrating what they actually know and can do in the real world. In short, we’ve perpetuated the belief that we can achieve equity by simply “doing” school better—and have relatively little to show for it.

What I have seen learner-centered environments do is explicitly and intentionally build into the educational experience and the environment children enter, the things that we know all kids need to be healthy, well-adjusted human beings.

Ulcca Joshi Hansen

Associate Director, Education Reimagined

In contrast, learner-centered education doesn’t see cognitive differences as deficits to be remediated but, rather, as strengths to be built upon. It helps young people understand how they learn best and allows them to create personally meaningful learning opportunities. It acknowledges that all kids won’t look the same when they finish school. And, it allows them to demonstrate and get credit for their learning in ways that make sense, rather than being constrained by the artificial structures of standardized tests.

This is in line with critical research suggesting that authentic assessment practices, such as exhibitions, portfolios, and authentic work products, may allow learners from different cultural contexts to better communicate what they know and are capable of doing.

There is the obvious and critical question here about how such an individualized system safeguards against low expectations for certain groups of learners. And, I look forward to exploring this in-depth in a future article. But, the high-level response is that I have seen learner-centered environments do this first and foremost by empowering learners to know and advocate for themselves. These environments also ensure that young people are known by multiple adults in their community who can engage them in authentic conversations about where they aspire to go and what they need to get there. This includes members of their family, multiple advisors, and mentors from the community.

Equity of the Human Experience

The second part of equity has to do with how well education supports a child in experiencing, and being supported in her fullness as a human being. All families want their children to become happy, well-adjusted adults who are able to build meaningful lives. There is a lot packed into that last phrase. It includes the need for them to be physically safe, mentally healthy, and emotionally supported by family, friends, and community. It means having a home, being able to make a living, having access to opportunities for professional and personal growth, and fulfillment.

By defining equity in terms of academic parity for so long, we reformed our system away from considering learners’ non-academic needs and actually deepened existing inequities. Families with power and privilege have always had a leg up in getting their kids to the outcomes identified above because they aren’t working against educational, economic, and social systems to get these things for themselves or their children.

They can navigate the public education system and choose districts or schools that are more focused on the whole child. They can opt out of the public education system altogether and pay for schools that are not as bound by the constraints of standardization and uniform notions of accountability. Or, they can access out-of-school experiences that complement a narrow educational experience in critical ways. These things are out of reach for families like Omayra’s and the families of the learners I taught.

What I have seen learner-centered environments do is explicitly and intentionally build into the educational experience and the environment children enter, the things that we know all kids need to be healthy, well-adjusted human beings: authentic relationships, a sense of purpose and relevance, and pride in and connection with their communities. These are the same things research shows help mitigate the impacts of poverty and instability and help young people cope with trauma and stress. These are also the same things learners need to engage and thrive academically.

There are emerging conversations about the need for change even within the conventional system…These initiatives are the result of people recognizing the mistake we made in stripping these components from the in-school educational experience in the name of focusing on academic outcomes.

Ulcca Joshi Hansen

Associate Director, Education Reimagined

Focusing on this human dimension helps close the “social capital” gaps our current system doesn’t address. If anything, reform efforts have perpetuated the idea that having kids walk and sit silently and conform to dominant cultural behaviors will lead them to success, regardless of their race, class, or culture.

We’re now seeing all the ways in which this isn’t true. Learner-centered education opens the doors of school and connects kids with people in the world beyond their immediate sphere. Whether they are the beneficiaries of dominant power structures or have to overcome them, the aim is to develop young people’s capacity to see, understand, and intentionally navigate these dynamics.

There are emerging conversations about the need for change even within the conventional system, and efforts around issues, such as socio-emotional and whole child learning, diversity, inclusion, and culturally-responsive practices. These initiatives are the result of people recognizing the mistake we made in stripping these components from the in-school educational experience in the name of focusing on academic outcomes.

My worry is that these initiatives are often designed and rolled out in ways that make them temporary patches on a system that was never designed to meet the human needs of children. This system was actually designed to perpetuate existing power structures. The vast majority of schools I see adopting such programs tack these things on in ways that don’t really go deep enough to make a big difference. They are implemented as a supplement to, rather than a transformation of, the conventional system. Rather than system-wide transformational training being given to every educator, it is often the responsibility of a single educator or small group of educators to ensure these practices are conducted on the side of the regular day-to-day schedule.

The places where SEL initiatives are really well implemented often sit right on the edge of the learner-centered mindset shift—if they haven’t made it—because the intentionality with which they focus on implementing SEL actually begins to transform how adults view young people and their role and relationship with them.

None of this is Easy (and it never has been)

Transformation—education or otherwise—isn’t easy. But, reforming our school-centered system hasn’t been easy either, and it’s incurred many unexpected costs. My journey has persuaded me that striving towards a learner-centered system will get us much further in our quest for equity than focusing our efforts on reforming our current system.

This means we need to take a two-pronged approach—working to improve our current system as much as possible for the learners who will have no other option, while also creating the space and time necessary for learner-centered practitioners to invent the new systems and structures needed to allow learner-centered environments to thrive and flourish within the public system.

I have an idea for a third frame in that education cartoon. In this one, a few kids will be happily looking over the fence aided by different sized boxes, or maybe by periscopes or drones. Others will be digging under the fence or climbing over it. And, still others will be painting it, taking it down, or even walking away to find a different view. This alternative frame would capture the mindset we need in order to ensure each child is recognized for who they want to be in the world and is supported in getting there. It’s the shift that will empower us and our children to build a world that respects and reflects the diversity of human potential.

I’m driven by Omayra’s observation that “schools don’t do nothin’ for nobody.” My vision is a system where Omayra is wrong.

New resources and news on The Big Idea!

×

We recently announced a new R&D acceleration initiative to connect and support local communities ready to bring public, equitable, learner-centered ecosystems to life.